The problem with Cambridge Analytica is not the privacy breach

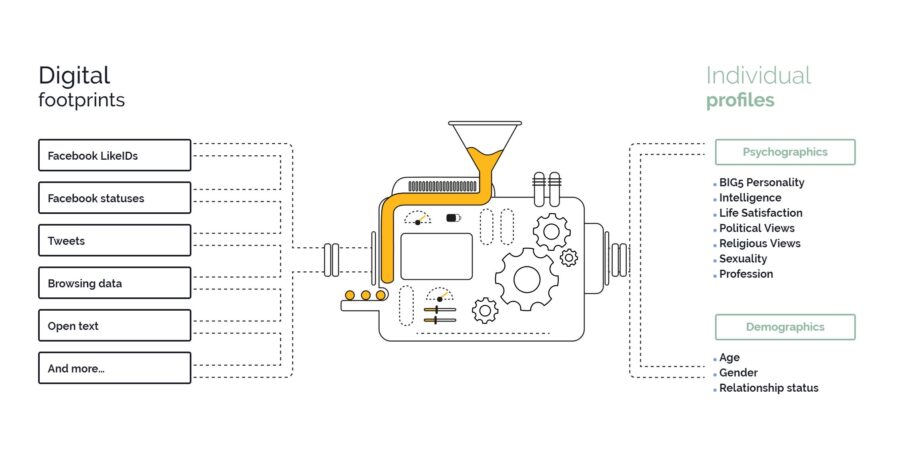

Thanks to a famous Vice article from April 2017, everyone, even those not acquainted with technology, has now an idea of how we are basically giving Facebook a map of our preferences, orientations, motivations, and even our psyche, by using it to share our interests, play games, answer quizzes and interact with other people. This data, in turn, is used by FB to present us with news feed items and ads that its algorithms classify as potentially interesting for us. These preferences, motivations and interests are called “psychographics”. Moreover, when you use 3rd-party applications and agree to use your FB account to gain access, you are also giving away your psychographic data.

Demographics VS Psychographics

Psychographics are the data about you that can’t be easily discernible from observation of your character, since it resides in your head, as part of your profile, preferences, motivations and idiosyncrasy. Demographics, on the other hand, can be obtained with simple observations. For example, from my Medium profile you may deduct that I am a male, Mexican, in my 30s, and author of this article, and by looking at my id card you know other data, such as my place of residence, or my birth date.

However, if an interested party wanted to know something about my political leaning, preferences or motivations, my id card is definitely not enough, so they will have 2 options:

- somehow convince me to answer dozens of surveys and personality questionnaires (most of which have been devised rigorously by psychology and sociology, some of which have been open sourced), or…

- trying to deduce them from the considerable trail of opinions, tastes and preferences I’ve left on FB, and comparing them to similar trails in a database of several other unsuspecting users.

With the help of technology option 2 will be better in terms of cost-benefit, even more so if this interested party wants not only my trail, but the trails of hundreds or thousands of users to target them all with suitable messages.

This interested party can now connect those data to a piece of actionable information, such as recommendations on content or types of messages. One way to do this is put forward by Dr. Michal Kosinsky, in his seminal work that served as the basis for CA’s products and business model, where he proposed methods to deduce concrete personality traits from the content you post, the posts you share, and the comments you make in FB. Still nothing wrong with this sort of work. Quite the contrary, it brings quantitative approaches to traditional psychology.

How did CA plan to use psychographics to influence the Mexican election?

Political Marketing will try to convince you to support this or that politician using messages you may empathize with, in order to establish a rapport with such politician, even though you might have never met them. These messages are usually designed using a mixture of quantitative and qualitative methods, like cohort analysis, focus groups, surveys, etc. Their effectiveness depends on the population sample they apply these artifacts to. A biased sample will result in biased conclusions, often with results contrary to those expected (see the infamous 1936 Literary Digest poll). We’re now in ‘questionable practices’ territory.

With CA, though, Political Marketing enters the data deluge era (we actively reject the “big data” term because oftentimes you don’t need it). By combining Dr. Kosinski’s work with widely available technologies, and taking advantage of the loose privacy policies of FB at that time, it was possible for CA to obtain thousands of profiles and their trails of activity, classify these users’ activity into personality traits, and then use their political marketing experience to cluster these classifications into groups. These clusters are then used to generate suitable messages that appeal to that group’s interests, motivations and idiosyncrasies, thus maximizing reach, scale and influence.

Political Marketing in the data deluge era means trading questionnaires and surveys for software pipelines that acquire, cleanse, process and analyze data on our activity trail left on social networks, and then recommend actions based on the results of this analysis.

Diagram of applymagicsauce.com, a trait prediction engine developed by University of Cambridge’s Psychometrics Centre. It bears no relation to CA, and they explicitly address ethical issues. For one, they ask that you upload the data and fully disclose how you got it.

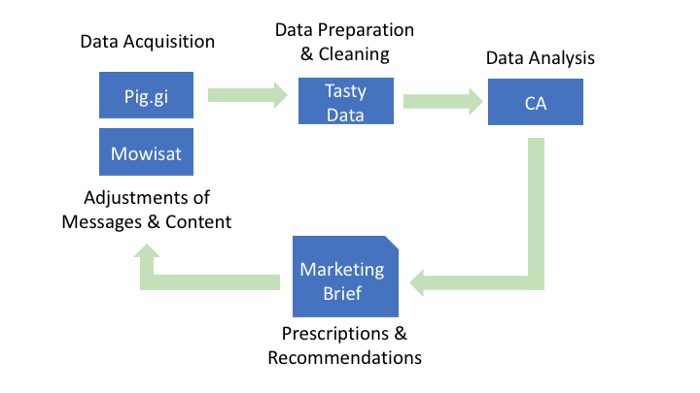

CA’s Data Pipeline in Mexico

In Mexico, their work is not a one-man-show as in UK or the US. They had help. Since they were already getting a lot of heat from the media even before coming into the country, they had to acquire, found, or set up different firms to serve at every stage of the data pipeline, in order to ease some of that bad rep they were getting. The following diagram shows their data pipeline as deducted by the research done by El Financiero, The Data Pub, and our collaborations with them.

This is the Data Pipeline CA set up in Mexico. Pig.gi and Mowisat’s involvement was exposed by El Financiero. Tasty Data’s involvement has not been verified and is part of our research.

In this pipeline, Pig.gi and Mowisat acted as the apps and services that required FB login in order to have access to users’ data. This data, we surmise, was then shared with Tasty Data, a now defunct firm dedicated to Data Analysis, and then finally shared with CA for analysis, classification and clustering. CA then produces a political marketing brief for the companies running these apps so they adjust and adapt their content, messages, posts and even memes on the FB pages they run, while at the same time giving everyone involved plausible deniability when asked what political party or actor they work for. The real power of this pipeline, though, lies in the fact that it gathers data on reality on time t, then alters reality with the results of the analysis, and then reobserves reality, looking for the effect of the actions to adjust actions for time t+1. Lather, rinse, repeat.

This sort of pipeline is the true mark of a real, well-built, world-class data science, analytics or machine learning project: observe reality, alter it, and reobserve it.

Echo Chambers as CA’s Divide-and-Conquer Strategy

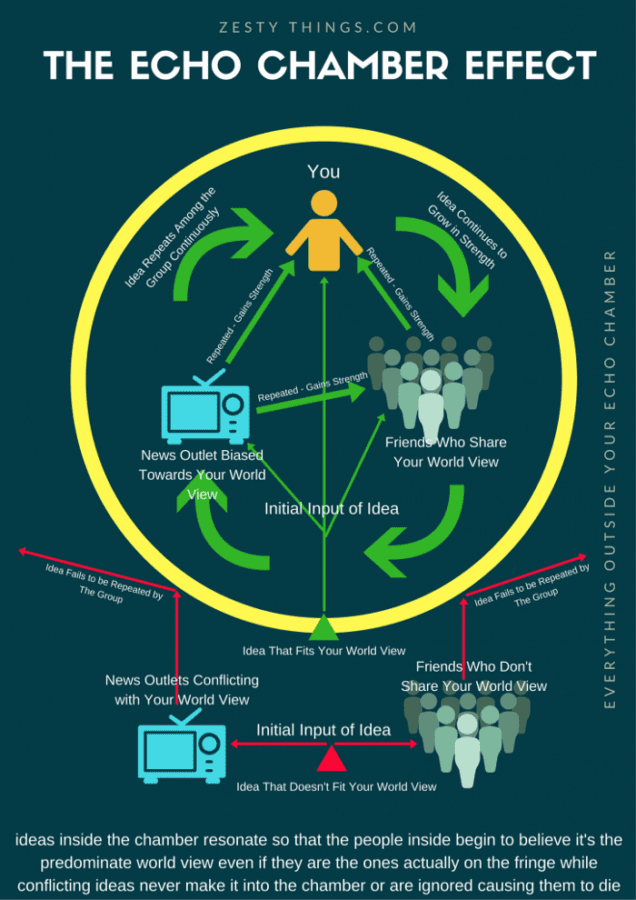

The end results of this pipeline are hyperpersonalized messages that attempt move certain electorate groups to a specific, coordinated action. Say, for example, that a strategy consists of moving Group 1 to avoid the ballots entirely, and Group 2 to go out and vote. This can be achieved by showing messages and content that make Group 1 feel their candidate is going strong and that victory is secure, while showing content that urges Group 2 they go out and vote and show their support. These messages effectively create echo chambers that can make those in them believe the whole world is defined by their preferences, motivations and desires, and hence everyone must surely share them. Echo chambers are particularly resilient, since opening ourselves to ideas opposite to ours causes high cognitive dissonance and stress. Apparently, we apply “fight or flight” reflexes not only to physical situations…. And it is here that we arrive to unethical territory.

“The echo chamber effect” by ZestyThings.com

The true damage of CA’s echo chambers in Mexico

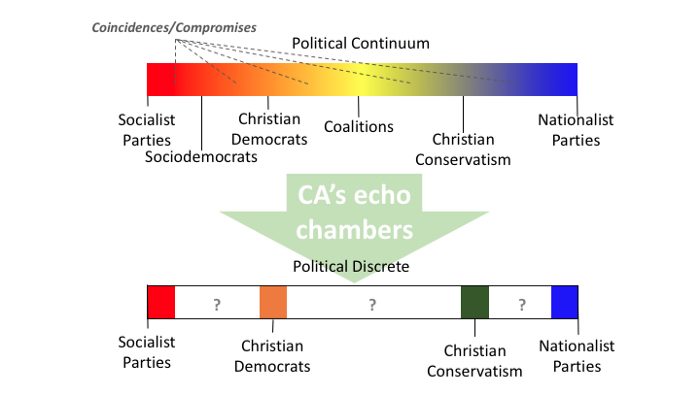

These echo chambers are damaging to democracy, among other things, because they attempt to discretize the political continuum, this is, isolate groups further and further until not only they become intolerant to other world views, but ignore their existence altogether, and therefore no coincidences nor common ground can be found between them. In our particular case, with weak institutions, anemic economic growth, dividing social issues, stagnant real wages and an endless string of structural problems, this strategy is particularly harmful.

This diagram attempts to explain how echo chambers created, fostered and enabled by CA weaken intersections between political preferences, hence debilitating the common ground required for building institutions

The political continuum means, for example, that a christian democrat has specific differences in how to solve particular social issues with, say, a center-right partisan, but it means they also share some common ground. This common ground is crucial to building alliances and coalitions, especially when it comes to a divided electorate, since they are the cornerstones of consensus and compromise.

Democracies are built on consensus (and sometimes compromise), which are, in turn, founded on coincidences and common grounds. Without them, we can’t build institutions, and without institutions, we can’t have democracy.

Attempting to fragment the electorate and isolate them in echo chambers is a direct attempt on our democracy. That an international firm is using the power of math, science and technology to achieve this in our country should offend us more than the privacy breaches this affair has revealed.

Final note on echo chambers, the Mexican federal elections of 2018, and a way to counter them

We are about to enter the most surreal elections in modern Mexican history. Parties are at their lowest credibility due to corruption scandals, but at their peak of financial resources. Electoral institutions work with outdated laws that have little teeth to bite into parties’ malpractices. The electorate is skeptical of authorities, and deeply divided on social and economic issues. In this scenario, any attempt to further divide opinion, whether it comes from an international firm, or the candidates’ campaign teams, should be considered as immoral, for it carries intent and full knowledge about the consequences of these actions.

In contrast, we also need to make our peace with the fact that this is how things work now, that political marketing has caught up with the times and the frontiers between technology, political science, sociology and math are now blurred, and that we must now be very aware of the intent and the consequences of this new way of campaigning while we consume content on social networks. 10 years ago, campaign strategies were devised, acted upon, and results were expected in months. It is now a cycle of days before a message is tested, adjusted and redeployed, leaving us with a very little window of time to become conscious of their effect.

In this context, the smartest way to counter the effect of these efforts is to get out of our echo chamber. If you follow Senator Bernie Sanders and agree with his political stance, try following, por example, Donald Trump. If you follow the ACLU, try following the NRA. The same applies to music tastes, reading preferences, and even the food you prefer, and it doesn’t have to be the exact opposite, just orthogonal enough that you yourself say “this isn’t me”. This way, the new data on you picked up by the pipeline will result in high variance, thus lowering the confidence with which you are classified, and hence removing you from the cluster, and once you have achieved that, you will be presented with content and messages in FB that come from other clusters, since the algorithms can’t really place you. Now, in order to keep it this way, continue feeding noise without a discernible signal to CA’s or FB’s algorithm, either avoid clicking on content from unverified sources, or click on all of them: if there is no variance with a pattern, there is no signal, no information, and hence no echo chamber for you.

If data is being used to influence your opinion, then mess with the data. It is, after all, yours.