This article has been updated, and now includes two new sections at the bottom (sections 4 and 5), featuring interesting results, more accurate approximations, and nice mathematical formulas involving prime numbers and the famous Euler constant. The last formula at the bottom of this article is remarkable.

The prime number theorem is a famous result in number theory, that characterizes the asymptotic distribution of prime numbers: For instance, the fact that the n-th prime number is asymptotically equivalent to n log n. By definition, two quantities f(n) and g(n) are asymptotically equivalent, denoted as f(n) ~ g(n), if the ratio f(n) / g(n) tends to 1 as n tends to infinity.

The standard proof of the prime number theorem is extremely long and complicated, and requires knowledge of advanced mathematical theories. Here we propose a short, elementary proof that even high school students can understand. To make it rigorous, there are a number of points that require a much deeper dive. So this proof is just a sketch, but it is rather intuitive.

1. Simple proof of the prime number theorem

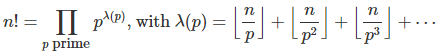

Let’s start with the Legendre formula for n! (factorial n), easy to derive:

Here the brackets represent the floor function. Taking the logarithm, we obtain

The rightmost sum is over all primes p less than or equal to n (here the set Q(n) denotes all primes less than or equal to n.) Note that these sums are actually finite: the terms vanish respectively when p > n or k > log n / log p.

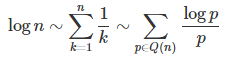

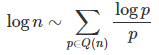

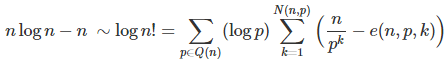

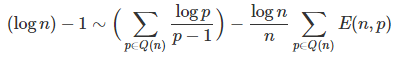

Since, based on the Stirling approximation, log n! is asymptotically equivalent to n log n, the above formula yields

Now, using the general algebraic lemma below, applied to the set Q of prime numbers, we conclude that the difference d(p) between the prime number p and the largest prime number smaller than p, is on average asymptotically equivalent to log p. It follows immediately that the n-th prime number is asymptotically equivalent to n log n. This completes the proof of the prime number theorem.

2. General Algebraic Lemma

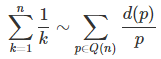

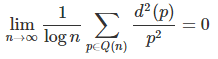

This is a classic algebraic result that applies to many sequences of slowly increasing positive integers, not just to prime numbers. If Q is an infinite set of positive integers, with Q(n) being the subset of all integers in Q that are less than or equal to n, then under rather general conditions described below, we have

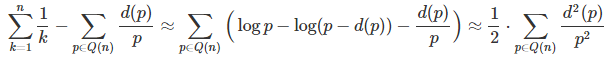

where d(p) is the difference between p and the largest element of Q that is smaller than p. I could not find a reference for this result, but it is rather intuitive, and it is probably an old theorem.The asymptotic equivalence is guaranteed if

and d(p) / p tends (on average) to zero as p tends to infinity. The above condition simply states that the difference between the left and right hand side of the asymptotic relationship, should be an order of magnitude smaller than log n as n tends to infinity. As long as this condition is met, even if there are increasingly large gaps among the elements in Q, then the result is valid. The proof is easy and based on the fact that the difference between the left and right hand side is well approximated by

especially for large values of d(p). When the gaps between the successive elements of Q are small (that is, when the d(p)’s are small) the result is even more obvious.

especially for large values of d(p). When the gaps between the successive elements of Q are small (that is, when the d(p)’s are small) the result is even more obvious.

3. Alternate solution

Here I propose a different path to arrive at the final result, though it starts with the same Legendre formula and subsequent asymptotic development.The alternate solution is as follows. In the formula

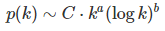

replace the k-th prime — let’s denote it as p(k) — by

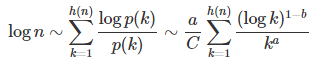

where C, a, and b are arbitrary constants, with a > 0. Of course this assumes that p(k) must have this relatively standard approximation. Then the asymptotic formula becomes

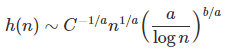

where h(n) is the number of primes less or equal to n. Using the asymptotic relationship for p(k), by inversion, one can find an asymptotic relationship for h(n), based solely on a, b, C, and elementary functions:

Then one must prove that C = 1, a = 1, and b = 1, for the last sum to be asymptotically equivalent to log n. This last part is just a pure calculus exercise that does not involve playing with properties of integers or prime numbers. It is obvious though, that if C = 1, a = 1, and b = 1, then the asymptotic formula is true.

4. Improving the prime number theorem

So far we only used first order approximations such as log n! ~ n log n. We can obtain more accurate asymptotic formulas by taking into account second and third order terms. For instance, a better approximation for log n! is log n! ~ n log n – n. Basil Gordon showed that you could obtain an elementary proof of the prime number theorem using this approximation (reference: click here and go to page 29 for the general context; for the actual result, click here.)

There is abundant literature about more accurate formulas for the distribution of prime numbers. The most popular one is based on the logarithmic integral. Here our goal is more modest: trying to use more than the first term in the Legendre expansion in an attempt to improve accuracy. Although we do not give an answer to this question here (we show how to do it though) we stumbled upon some interesting problems and solutions.

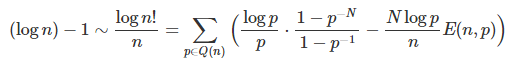

If we include more terms both from the log n! approximation and from the Legendre formula, we get

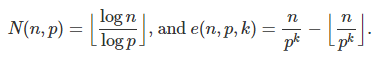

where

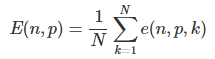

The quantity e(n, p, k) is between 0 and 1, and when averaged, it converges to a value close to 1/2; details are discussed in the next section.

This can be rewritten as

where N = N(n,p) and

with E(n,p) between 0 and 1, and indeed closer to 0.5. This can be further approximated as:

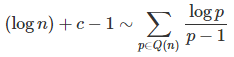

The computation of E(n, p) is a tricky part, though we provide some hints in the next section. In a nutshell, assuming the average value of E(n,p) is equal to a constant c (slightly below 0.5) then the last sum is asymptotically equivalent to c |Q(n)| ~ c n / log n where |Q(n)| is the number of elements in Q(n). This yields the simplified formula

with 1 – c close to 0.577 (Euler’s constant) based on computing the previous sum over the first million primes. See next section for details.

Can this formula be used to get a more accurate version of the prime number theorem? Maybe, but it might not be easy. Maybe it could lead to something like Dusart’s inequality, stating that for n > 5, the n-th prime p(n) satisfies p(n) < n log n + n log log n.

5. Interesting problems

In this section we describe two problems related to our discussion

Average of fractional parts

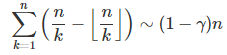

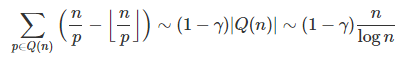

Sums involving fractional parts have been studied for a long time, and interesting results have been obtained. For instance, it is well known that

where g is Euler’s constant, see here for details. A similar formula for all integers (not just for the primes), involving the same 1 – g factor, also holds:

More on the subject can be found here. More on the generalized Euler constant can be found here and here. Since we are dealing here with sums such as E(n,p) that are connected to Euler’s constant, it is no surprise that 1 – c in our last result, is Euler’s constant, though it remains to be formally proved.

Sums involving primes

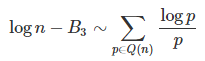

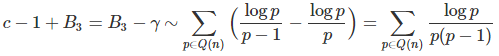

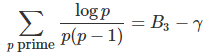

Combining the last formula in section 4 with the following well known result involving the constant B3 = 1.3325822757… (click here and here for details)

we get

Taking the limit as n tends to infinity, we eventually get the following convergent series, where the sum is over all primes:

It is quite remarkable that this last result was obtained by substracting two diverging series for which only asymptotic results are available. This is one of the few known results (with exact solution) for converging series involving primes. A more general one can be found in Don Zagier’s article (Newman’s Short Proof of the Prime Number Theorem, see section IV. )

Related articles

- Fascinating Facts and Conjectures about Primes and Other Special Nu…

- Factoring Massive Numbers: Machine Learning Approach

- 88 percent of all integers have a factor under 100

- Representation of Numbers as Infinite Products

- A Beautiful Probability Theorem

- Three Original Math and Proba Challenges, with Tutorial

- Curious formula generating all digits of square root numbers

- Seasons in Binary Star Planetary Systems