Summary: Just how accurate are algorithms at spotting fake news and are we ready to turn them loose to suppress material they don’t find credible. Here are some considerations and stories about some of the companies trying to build these fact-checkers.

Which of the following headlines is fake?

a) Police Investigating Clinton-backed Pizza Shop Pedophilia Ring

b) The Pope Endorses Donald Trump for President

c) Eastern European Fake News Sites Impact Pro-Trump Anti-Clinton Voter Sentiment

The first two are in fact fake. You may actually have seen them during last fall’s election coverage. The third headline however is true, but not with the implications you may think.

Depending on which conspiracy theory you subscribe to, either the Russian government or someone else produced huge volumes of pro-Trump fake news with the intent of influencing the election. What BuzzFeed discovered last November is that at least 140 pro-Trump web sites were being run out of one small Macedonian town of Veles (population 45,000 and no not part of Russia) by a relatively small group of teens and young adults cashing in on the Google AdSense pay per click revenue stream.

Their motive – strictly the cash. Apparently you can have a pretty good life style in Veles from just this source. Their political knowledge – none beyond the fact that these extremist web sites once on Facebook drew tons of cash generating clicks.

So what’s driving fake news is the change in the fundamental business model of news reporting, from a few well fact-checked news agencies to the new internet enabled anyone-can-write-a-headline-and-get-paid free for all. Essentially version 2.0 of the Nigerian prince email racket.

There are lots of us who understand the inherent danger in this proliferation of fake news. What we want to look at here is how much progress we’ve made toward using data science to be able to detect fake news and do something about it.

Not Everyone Has the Same Motives for Finding Fake News

You might think that it’s individual discriminating readers who most want to be protected from fake news. There may be a few but the reality is that pretty much everyone mistakenly believes they can tell true from false, and fewer of us are willing to take several extra clicks to run an app that might flag content as true or false. The real stakeholders in this battle are all motivated by money.

- Aggregators like Facebook and Google are already suffering from advertisers pulling their ads that were programmatically placed on sites that proved to provide fake news or other offensive content. Beyond that they have general reputational risk with their users who may visit less often if they are exposed to blatantly false or offensive material.

- Legitimate news agencies like Thomson Reuters or any of the major news broadcast or print organizations who take raw information feeds and convert it to news stories. They would suffer greatly if their material started to be compromised by falsehoods.

What Does Fake News Look Like

A further problem is that fake news doesn’t all look alike. In fact you may need separate models to identify targets in different categories. Brennan Borlaug, one member of small team of grad students at UC Berkeley who have tackled this problem classifies them this way:

A further problem is that fake news doesn’t all look alike. In fact you may need separate models to identify targets in different categories. Brennan Borlaug, one member of small team of grad students at UC Berkeley who have tackled this problem classifies them this way:

- Clickbait — Shocking headlines meant to generate clicks to increase ad revenue. Oftentimes these stories are highly exaggerated or totally false.

- Propaganda — Intentionally misleading or deceptive articles meant to promote the author’s agenda. Oftentimes the rhetoric is hateful and incendiary.

- Commentary/Opinion — Biased reactions to current events. These articles oftentimes tell the reader how to perceive recent events.

- Humor/Satire — Articles written for entertainment. These stories are not meant to be taken seriously.

Can Data Science Spot Fake News

This has become a hot and potentially profitable area and many companies are working on this. We’re going to highlight a few that have particularly interesting stories.

Full Fact

Full Fact is a UK based fact-checking outfit recently granted $50,000 by Google to immediately start developing an automated fact-checking helper. Will Moy, the director of Full Fact says computers can start helping human fact-checkers soon, but that a perfect system is still far off.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about Full Fact is that its plan is based on their belief that there are fundamentally two distinct data science architectures that can be applied. The one they did not choose is the more traditional path of NLP similar to SPAM detection.

The path adopted by Moy is to build a Watson-like platform that can parse facts floating around the world as unstructured social media data and determine if they are true or false. This would mean loading the system with a huge volume of curated known-true facts then comparing new material using the logic of Question Answering Machines (QAMs) like Watson.

Watson

Well what about Watson? This seems like a problem made to order for IBM’s QAM. IBM has in fact spent several years working on ways that Watson could help users distinguish fact from fiction. In the spring of 2016 IBM released the beta of Watson Angles complete with a corpus of 55 million previously published news articles.

By late 2016 however IBM had pulled back its prototype. According to Ben Fletcher, senior software engineer at IBM Watson Research who built the system, it was unsuccessful in tests – but not because it couldn’t spot a lie.

“We got a lot of feedback that people did not want to be told what was true or not,” he says. “At the heart of what they want, was actually the ability to see all sides and make the decision for themselves.”

Remember, that aside from the UX implications of Fletcher’s comment, a successful Watson implementation requires constantly adding to and deleting from the corpus of knowledge. This would be a huge human undertaking to attempt to catalogue all of what is ‘true’ in the news. In other more successful Watson implementations the knowledge base like tax law or sample images of cancerous tumors simply doesn’t change as fast as the news.

Thomson Reuters

Thomson Reuter’s 2,500 journalists in 200 countries take in unfiltered news articles from the web along with the full social media feeds of Twitter and other major channels, and craft valid and fact-checked news articles. As a trusted source, a failure to spot a fake source would be a major failure. But being slow to report a breaking newsworthy event would also be a fail.

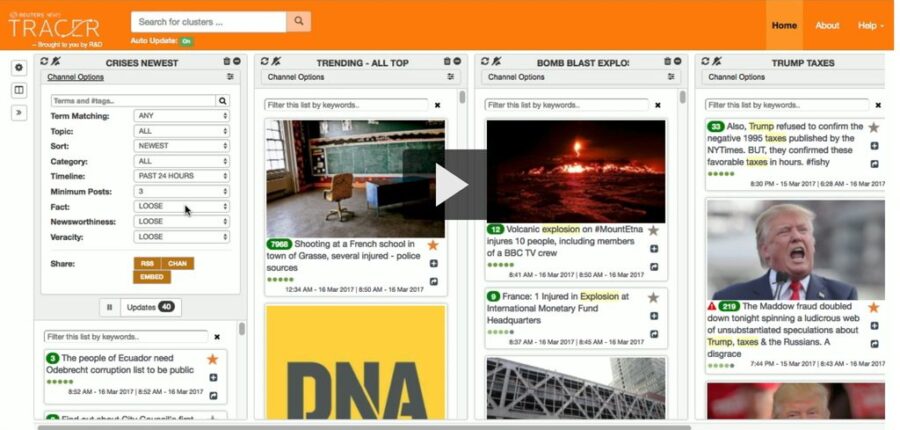

At the Strata+Hadoop conference in San Jose in March, Khalid Al-Kohani, head of R&D demonstrated Tracer News, the most complete and sensitive system I have yet seen. Gone are the days when newspaper men hung out at the police station or the court house hoping for a scoop. Now they sit at large displays with constantly updated summaries of themes consolidated via NLP and some very sophisticated logic.

In the screen shot above, the journalist defines several ‘channels’ or themes he is interested in, for examples ‘crises’, or ‘trending’, or ‘Trump taxes’. As Al-Kohani explained, within 40 ms the algorithmically driven platform performs these steps:

- First filters for noise, selecting only those feeds that look like events.

- Adds metadata such as topics, entities, relationships, and locations allowing the input to be clustered into the basic who, why and where of events.

- Determines if the event is newsworthy or merely subjective reporting.

- Is it an assertion or statement of fact or is it an opinion.

- Assigns a veracity score by looking at characteristics of the source and author such as –

- Are there multiple sources

- Are the sources known to be good

- What is the history of these sources, for example do they participate in rumors or conspiracy theories, and what is the civility of their discourse.

A variety of sensitivity filters are provided for the user along with a visual flag indicating both newsworthy and true.

Al-Kohani says their analysis of news stories has proven 84% accurate. And with a sample of only 5 Tweets they can differentiate between rumor and fact with 78% accuracy.

Tracer News has been two years in development and is used internally as well as by Reuter’s financial customers.

Classify News – Making News Credible Again

Our final entrant is focused on the individual reader providing a tool that you can use to score the veracity of an article by entering its URL. These four grad students, Brennan Borlaug, Sashi Gandavarapu, Talieh Hajzargarbashi, and Umber Singh built this classifier as the Capstone project for their UC Berkeley’s Master of Information and Data Science program. You can access the classifier and test for yourself here (www.classify.news).

Their approach highlights one of the other complexities of fake news identification, the need to consider both content and context. Context is frequently the element most difficult to model.

This team ultimately produced an ensemble classifier using Naïve Bayes for content and Adaptive Boosting for context. Their training set of about 5,000 articles is on the small side but their site claims 84% accuracy based on voluntary user provided feedback.

The two fake news samples I tested scored 60% and 67% likely to be non-credible respectively. Right answer though the score does not give me a huge confidence margin.

Human Fact-Checkers Are Still the Gold Standard – Most of the Time

Human fact-checkers, either in house at major new organizations or at outfits like Snopes and Politifact are still way ahead of purely machine learning solutions using a logical approach modeled by Trace News described above. But humans are expensive.

Snopes reports that a seemingly simple claim can take hours while a seemingly complex one might take just 15 minutes. Currently there’s no way to predict required manpower. Like speech recognition and image processing before it, the gap is likely to narrow as we press toward automating as much of this process as possible.

Perhaps the most important question is whether we will ever reach a point where it is acceptable for an algorithm to automatically suppress a news story. There will always be false positives and false negatives. Is 5% too great? Is 1% too great? It’s one thing to misclassify a photo or misinterpret speech, but errors or unintentional bias here has freedom of speech implications that will not remain hidden very long once they arise.

Here’s a final story about why we’re not ready for this yet. In mid-2016 Facebook was using a team of human editors to curate its Trending News section. In addition to deciding what was ‘trending’ they were also charged with fact-checking and linking them to a news story from a credible source.

Here’s a final story about why we’re not ready for this yet. In mid-2016 Facebook was using a team of human editors to curate its Trending News section. In addition to deciding what was ‘trending’ they were also charged with fact-checking and linking them to a news story from a credible source.

By the time the presidential election got underway however Gizmodo broke the story that these editors were instructed to suppress news about conservative topics. Although initially denying the practice, within months the editors had all been fired and replaced by algorithms.

All did not go well. Within days the Trending News featured a fake news story that Megyn Kelly had been fired from her job as a Fox News host for being a “traitor” and supporting Hillary Clinton for president. Quickly it was taken down but not before being seen by millions. Since stories posted there come with the implied approval of Facebook, the reputational damage was done.

‘Well managed’ humans versus algorithms. We’ll have to watch a little longer to see how this develops before we give up evaluating stories for ourselves.

About the author: Bill Vorhies is Editorial Director for Data Science Central and has practiced as a data scientist and commercial predictive modeler since 2001. He can be reached at: