Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis (1818-1865) was a Hungarian physician and scientist, now known as an early pioneer of antiseptic procedures.

Described as the “saviour of mothers”, at 1846 Semmelweis discovered that the incidence of puerperal fever could be drastically cut by the use of hand disinfection in obstetrical clinics (this fever was common in mid-19th-century hospitals and often fatal).

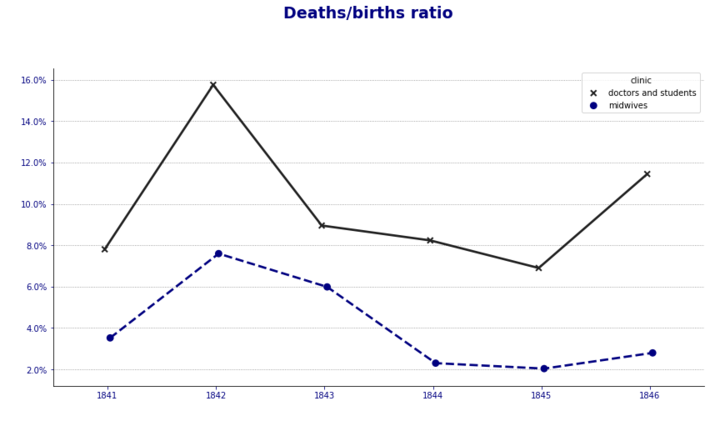

He observed that in clinics where midwives worked the death ratio was noticeably less than in clinics with educated doctors.

Dr. Semmelweis started his work to identify the cause of this tremendous difference. After some research, he found that at “clinic 1” doctors performed autopsies in the morning and then worked in the maternity ward. The midwives (clinic 2) didn’t have contact with corpses.

Dr. Semmelweis hypothesized that some kind of poisonous substance was being transferred by the doctors from the corpses to mothers. He found a chlorinated lime solution was good to remove the smell of autopsy and decided it would be ideal for removing these deadly things.

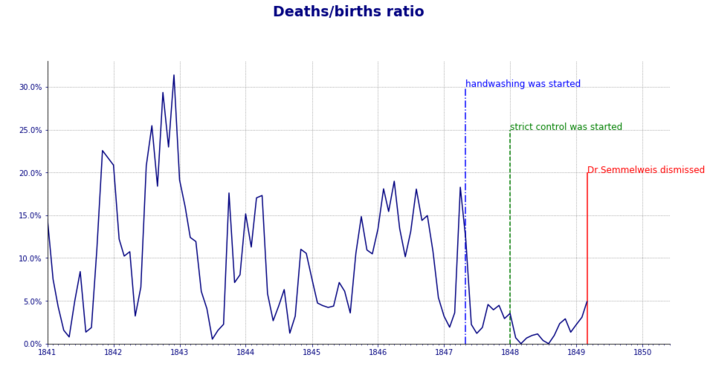

During 1848, Semmelweis widened the scope of his washing protocol, to include all instruments coming in contact with patients in labor, and used mortality rates time series to document his success in virtually eliminating puerperal fever from the hospital ward.

Semmelweis had the truth but it was not enough.

Semmelweis had the truth but it was not enough.

Doctors are gentlemen and a gentlemans hands are clean. – said an american obstetrician Cahrles Meigs and this phrase shows us a common opinion that time.

It is dangerous to be right in matters on which the established authorities are wrong.

Voltaire

Semmelweis paid dearly for his heretical handwashing ideas. In 1849, he was unable to renew his position in the maternity ward and was blocked from obtaining similar positions in Vienna. A frustrated and demoralized Semmelweis moved back to Budapest.

He watched his theory be openly attacked in medical lecture halls and medical publications throughout Europe. He wrote increasingly angry letters to prominent European obstetricians denouncing them as irresponsible murderers and ignoramuses. The rejection of his lifesaving insights affected him so greatly that he eventually had a mental breakdown, and he was committed to a mental institution in 1865. Two weeks later he was dead at the age of 47succumbing to an infected wound inflicted by the asylums guards.

Semmelweis’s practice earned widespread acceptance only years after his death when Louis Pasteur confirmed the germ theory.

Semmelweiss data was great – truthful, valuable, and actionable, but the idea failed.

Let’s try to understand why.

1. Semmelweis published his “The Etiology, Concept, and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever” in 1861. But over 14 years, from inventing to publishing, the medical community misinterpreted and misrepresented his claim.

Lesson 1: keep your data clear and timely.

2. Semmelweis was not able to understand why people wouldn’t accept his advice. He insulted other doctors, became rude and intolerant.

Lesson 2: always remember about cognitive bias named “curse of knowledge” – know your audience, strive to understand them. And look for open-minded allies.

3. He felt emotion instead to evoke them.

Lesson 3: Use logic and reason to make your job, but use narratives to show it.

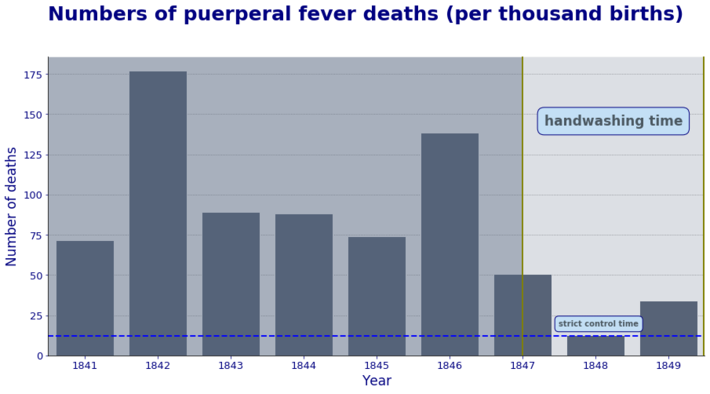

4. Semmelweis had his data only as data tables. Not many people can read that.

Lesson 4: good data visualization is the key.

Let’s try to use this – I’ll show the same data but in other way:

Data and data analysis are the flesh and blood of the modern world, but this alone is not enough. We must learn to present the results of the analysis in such a way that they are understandable to everyone – “sticky” idea and clear visualization are the keys.

More information and code in my repo at GitHub.