After reviewing 8 great ETL tools for fast-growing startups, we got a request to tell you more about open source solutions.There are many open source ETL tools and frameworks, but most of them require writing code. Since data engineers are not necessarily good programmers, you can try visual ETL to directly connect them with data. We asked Dmitry Dorofeev, Head of R&D at Luxms Group, to tell us about his experience with comparing Apache NiFi and Streamsets.

***

Our team has recently faced a boring data integration problem: when some data is stored in Hadoop, some in Oracle, and a little bit is in Excel. The goal was to ETL all that data into Greenplum and finally provide some BI on top of it.

We quickly found 2 mainstream open source ETL projects: Apache NiFi and Streamsets, and it seemed an easy task to choose one product out of the two. In no way was it easy. I know that better than anyone since I was responsible for the product evaluation and the final choice. In this post, I’d like to share my experience and maybe save days of your life.

Spoiler: There is no silver bullet. Apache NiFi is not necessarily better than Streamsets, nor Streamsets better than NiFi. Everything has its pros and cons. This post is my personal experience with these tools as a novice user without any introductory training.

Dataflow Programming

Programmers, analysts, and even managers often draw a box and arrow diagram to illustrate some flows. You know what? You can even use these boxes and arrows to create programs. We can track such attempts back to the 1960s when the Dataflow Programming paradigm was born in MIT.

Today, we have tens of Dataflow Programming tools where you can visually assemble programs from boxes and arrows, writing zero lines of code. Some of them are open source and some are suitable for ETL.

Yes, you don’t have to know any programming language. You just use ready-made “processors” represented with boxes, connect them with arrows, which represent exchange of data between “processors,” and that’s it.

There are three main types of boxes: sources, processors, and sinks. Think Extract for sources, Transform for processors, and Load for sinks.

What can be a source? Almost anything: files on the disk or AWS, JDBC query, Hadoop, web service, MQTT, RabbitMQ, Kafka, Twitter, or UDP socket.

A processor can enhance, verify, filter, join, split, or adjust data. If ready-made processor boxes are not enough, you can program on Python, Shell, Groovy, or even Spark for data transformation.

Sinks are basically the same as sources, but they are for writing data.

Apache NiFi vs StreamSets

When we faced yet another customer with complicated ETL requirements I decided to try visual dataflow tools. Visual might be attractive even if you use Singer, data build tool, or other handy open source ETL tools, right?

Luckily, there are two open source visual tools with the web interface: Apache NiFi and StreamSets Data Collector (SDC). NiFi was donated by the NSA to the Apache Foundation in 2014 and current development and support is provided mostly by Hortonworks. SDC was started by a California-based startup in 2014 as an open source ETL project available on GitHub. The first release was published in June 2015.

Both products are written in Java and distributed under the Apache 2.0 license.

Here are some stats from GitHub for early 2018:

|

Metric |

||

|

Forks |

783 |

914 |

|

Stars |

811 |

405 |

|

Releases |

57 |

113 |

|

Version |

1.5 |

3.1.0.0 |

|

First release year |

2007 |

2015 |

Architecture and features

Both tools encourage creation of long-running jobs which work with either streaming data or regular periodic batches. You can create manually managed jobs, but they might be tricky to set up. This is the greatest surprise and mind-shifting feature I personally had with these tools.

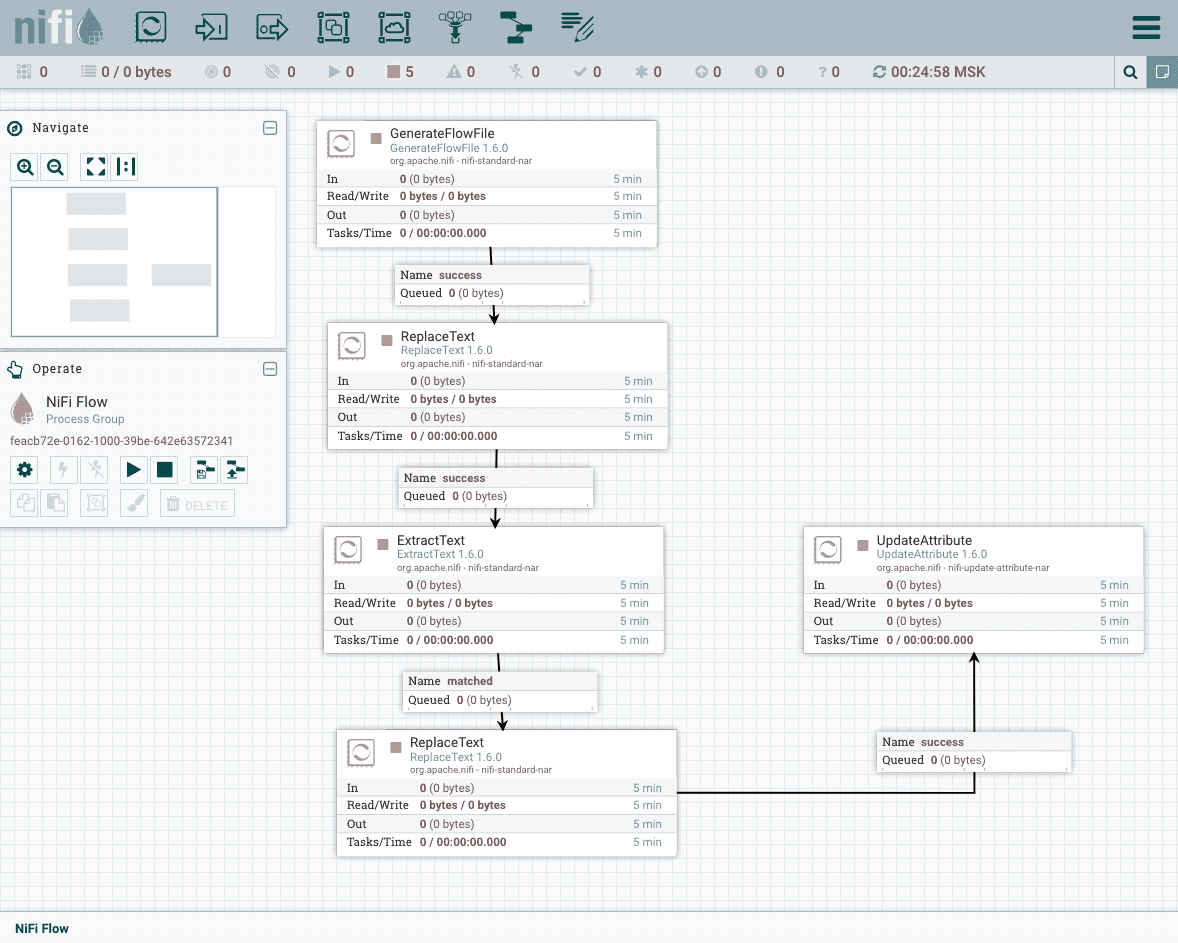

Apache NiFi

Apache NiFi has a well-thought-out architecture. Once data is fetched from external sources, it is represented as FlowFile inside Apache NiFi dataflows. FlowFile is basically original data with meta-information attached to it. You can easily process not only CSV or other record-based data, but also pictures, videos, audio, or any binary data.

A processor usually will have 3 outputs:

- Failure. If a FlowFile cannot be processed correctly, the original FlowFile will be routed to this output.

- Original. Once an incoming FlowFile has been processed, the original FlowFile is routed to this output.

- Success. FlowFiles that are successfully processed will be routed to this relationship.

You can terminate outputs with checkboxes, so Apache NiFi will ignore terminated outputs and will not send any FlowFiles there.

Another handy feature is Process Groups. When a dataflow becomes complex, you can combine your dataflow elements into Process Group, which is graphically represented in the UI in the same way as standard processors. It behaves as a processor, so you can build very complex dataflows recursively.

Controller Service is something that exists outside of your dataflows, but provides some useful information for your processors. It might be SSL certificates, JDBC connection and pool settings, schema definition, and so on. The idea is that rather than configure this information in every processor that might need it, the controller service provides it for any processor to use.

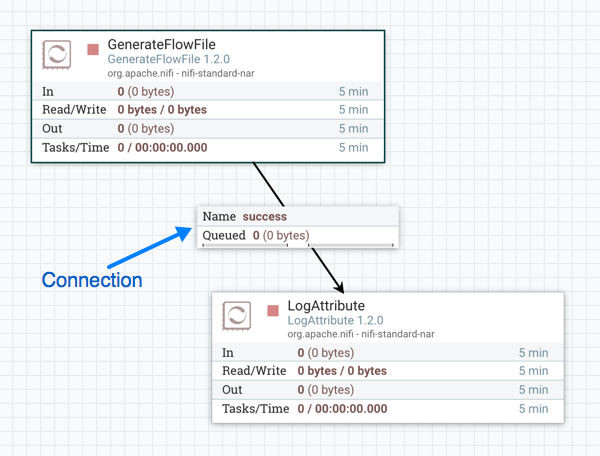

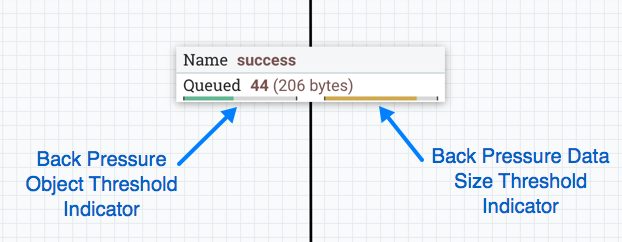

Processors are connected with… well, connections. Usually connections are just arrows, but not so with Apache NiFi. Every connection arrow has a small widget attached to it, representing a queue with back pressure and can be configured individually.

For example, if the LogAttribute processor becomes slow or freezes for some reason, FlowFiles generated by the GenerateFlowFile processor will be queued in the connection. After some time, back pressure will pause the GenerateFlowFile processor until the queue goes below the configured threshold.

If you are not yet impressed, how about different queue policies like FIFO, LIFO, and others you can apply to queues in connections?

Data Provenance is a Big Brother service which records almost everything in your dataflows as they process data. This is very handy, as you have recorded history of how your dataflow performed, including saved content of the FlowFiles. But that comes with a price, you should have enough disk space to keep the required backlog of provenance data.

Even with these awesome features and great architecture, I was not very comfortable with the Apache NiFi user interface. It is definitely usable, but not sexy.

StreamSets Data Collector

Then, I tried Streamsets.

Processors in Streamsets exchange records. That means that everything you ingest into Streamsets is converted automatically into the standard record-oriented format and all processors can handle it as a stream of records. There are no queues in between processors, at least, they are not represented visually, like we saw it in Apache NiFi.

In Apache NiFi the same processor should have different versions of itself to handle different formats. One version for CSV, one for JSON, and another for Avro, for example. You might guess that it is not very user and developer friendly. This was addressed in Apache NiFi 1.5, where most processors are using the Avro format, so you should convert to Avro early and it will be almost the same experience as in Streamsets after that.

To change processor settings in Apache NiFi you must stop the processor, while in Streamsets you must stop the whole dataflow.

That means that you always start your dataflow from the beginning after you make any changes in it with Streamsets. With Apache NiFi you have a chance to stop a misbehaving processor, fix it, and start again. Hopefully, queued FlowFiles will be sent to the fixed processor and you will not miss the data.

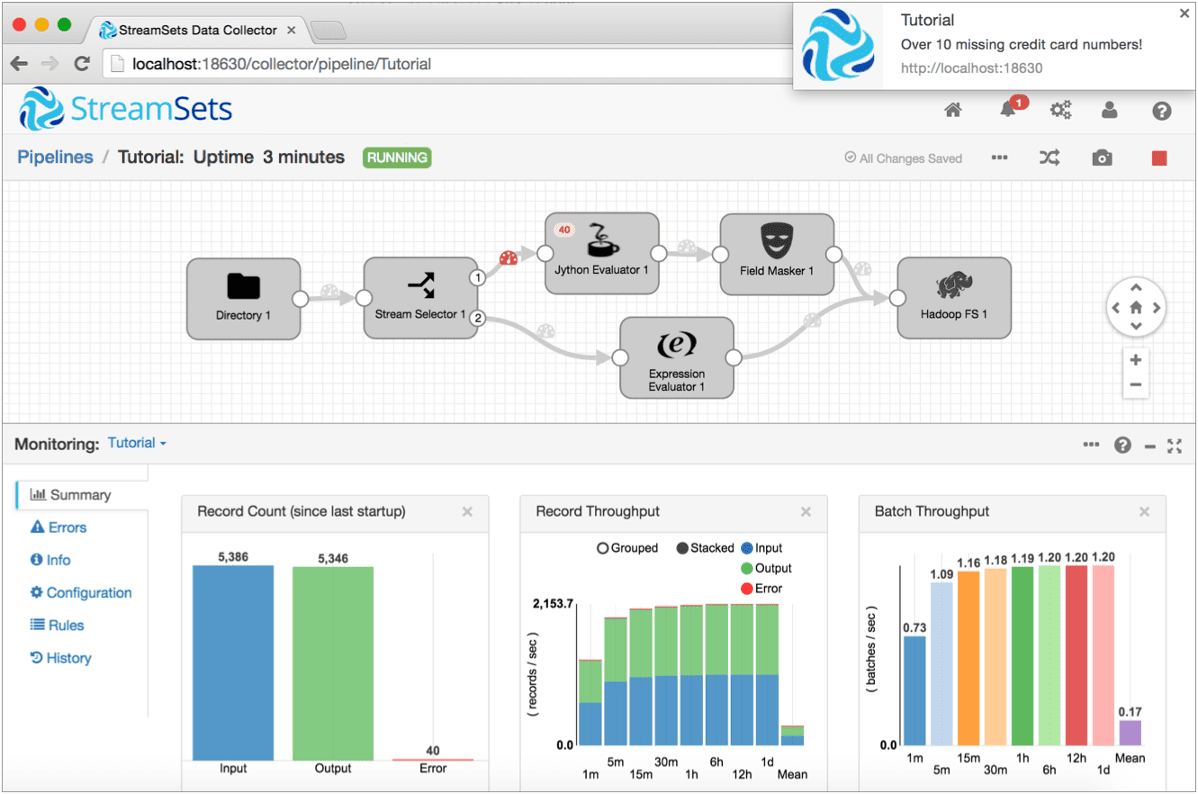

But that doesn’t mean that Streamsets dataflows are harder to debug. Actually it is easier, you have a nice-looking live dashboard displaying a lot of statistics for every processor while your dataflow is running. Errors are cleanly presented as red numbers on the processor icon and you can see individual errors for every faulty record with a mouse click. You may even put record filters on the connections between processors to inspect records in question. Filters can be applied while your dataflow is running, so I used it as live debugging tool.

Streamsets has 4 processor types:

- Origins: they get data from the external sources. You may have only one Origin Processor in your dataflow.

- Processors: data transformers.

- Destinations: they save data to the external systems or files.

- Executors: they process events, generated by other processors.

Some of the Streamsets processors may generate events, including errors. You should use special processors called Executors to handle that. For example, there is Email Executor, which can send emails when an error has occurred.

I am definitely more happy with the clean Apache NiFi architecture with just Processors and Controller Services, but the Streamsets design is also fine and can be quickly picked up.

UI

Apache NiFi

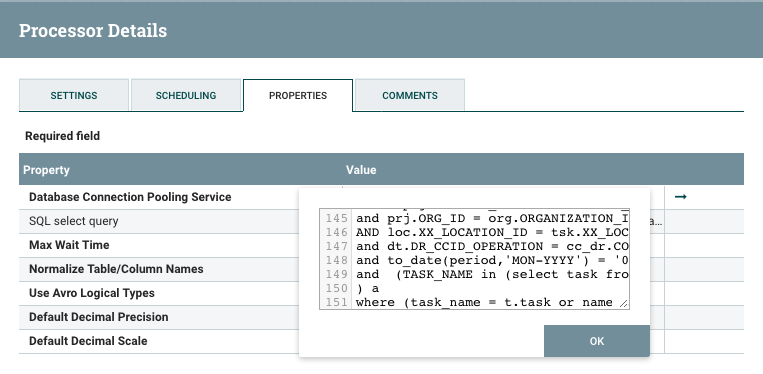

There is not much to say about the Apache NiFi UI. It feels spartan, and it is very easy to follow, thanks to the great architecture with minimum concepts. Probably the only drawback I discovered is that Apache NiFi will not autosize text fields for your long SQL queries, so you will have to manually resize popup text fields every time you want to edit it.

Streamsets

Streamsets has a more attractive UI, but it is not perfect as well.

The first thing I quickly get annoyed with is the absence of Controller Services, especially for JDBC settings. You need to fill in all JDBC settings for every processor that reads data from the same JDBC source. There is just no user-friendly way to reuse such information.

Before you can run your dataflow, Streamsets will check each processor inside your dataflow to make sure all processors are correctly configured. It sounds like a good thing, and it helped me sometimes, but other times – harmed me. In Apache NiFi you can have disconnected processors and I usually leave them so for debugging purposes. In Streamsets you can not do the same, since all the processors must be connected to make dataflow pass validation.

Another annoyance is that you can not select several processors at once. At least I was unable to do so. Moving a dozen processors and reorganizing them one by one on the screen can make you mad.

Streamsets has syntax highlighting for SQL which is a nice feature, but not always useful. Our data engineer creates heavy SQL queries which can easily be a hundred lines long. The syntax highlighting process becomes slow and that results in another annoyance. If you edit the last lines of the long SQL query the caret unexpectedly moves to the beginning and what you type appears on the first line.

Conclusion

I made a very brief introduction to Apache NiFi and Streamsets. They have plenty of useful features not covered in this blog post. Even if you do not find the required built-in or third-party processors, you can always use Python, Javascript, R, or even Apache Spark to program your complex data transformation logic in the Apache NiFi or Streamsets dataflows.

Both Apache NiFi and Streamsets are mature, open source ETL tools. They have very similar functionality and the only way to make a concise choice is to try both! That’s what I did. Even after 3 months of running both products I can not see a clear winner.

For me, live monitoring is the single feature in Streamsets that outweighs all its small glitches.

Apache NiFi

Pros:

- Clean and well-thought-out implementation of the dataflow programming concept

- Can handle binary data

- Data Provenance

Cons:

- Spartan User Interface

- No live monitoring/debugging features with per-record statistics

Streamsets

Pros:

- Live monitoring/debugging features with visual per-record statistics for every processor

- Sexy UI

- Well-suited for record-based data and streaming

Cons:

- You need to stop the whole dataflow to edit a single processor configuration

- No reusable JDBC configuration for processors

The original post appeared here.