Source: see last section in this article

Of course this question begs for the answer that it is both an art and a science. I view it more like craftsmanship. This article discusses my opinion on the subject.

We need to start by defining what machine learning is, or more precisely, what kind of work it entails. I broke it down into three types of activities, corresponding to different types of machine learning professionals or job titles. Many practitioners spend some amount of time, in various proportions, on any of these activities.

- Level 1: Professionals in this category are end-users of machine learning platforms or software, and typically their coding abilities are limited, and rarely needed. They use the tools as black boxes, and may not even know (or only superficially) the details of the techniques involved. They have the ability to interpret the output of the platforms that they use, to fine-tune parameters, and the ability to compare the performance of various platforms and techniques. Examples include business analysts, or software engineers asked to integrate algorithms developed by data scientists (those in level 3), into production mode.

- Level 2: In this category, I include people using machine learning tools and platforms, with a serious understanding as to how they work, and typically interacting with these platforms as builders and developers, mastering some programming languages to interact with these tools in the most efficient way. They typically don’t build new, complex algorithms, from scratch. But they know how to use existing ones to address the problems at stake, within the framework of the platforms that they use.

- Level 3: These people may not necessarily know that much about the tools mentioned in the previous levels, as they develop their own algorithms from scratch, typically to solve new problems not properly solved by the above platforms. They master some programming languages and their libraries (usually including Python), and are experts in algorithm design and optimization.

There can definitely be art involved at any level. However, I prefer to use the word craftmanship. As opposed to art which serves no purpose here except beauty, craftsmanship is the quality of design and work shown in something made by hand. It must serve a practical purpose, and it is usually shows as the signature of a professional proud to deliver high quality work, be it a piece of furniture or a piece of code.

At level 1, craftmanship shows as mastering the platform at a high level, sometimes even better than those who created it, and being able to leverage it in astute ways, and discovering tricks that few are aware of, to further optimize the work. At level 2, it can mean writing beautiful code, not for its own beauty but for the way other people are going to see it: achieving remarkable performance with some astute, elegant code nobody thought about it before. It can mean understanding the inners of these platforms, and being able to circumnavigate their inherent glitches. At level 3, it could mean designing an algorithm that is able to extract more information from data than you would theoretically be expected to, based on the law of entropy. For instance designing unexpectedly sharp confidence intervals that nobody thought could be possible (see my book on new statistical foundations, page 132, and available here).

What about machine learning as an art?

Since art in this context does not generally bring added value, you are going to see craftsmanship more so than pure art. That said, very talented professionals may decide to bring their work to a whole new level and secretly incorporate art into it (much better than incorporating back doors, or unethical biases!) Nobody may recognize the art hidden in their work for a long time, and they will never gain a financial advantage from it, but instead they gain a personal satisfaction of being able to deliver high quality work on time, yet incorporating art into it. Some of the art can be recognized sometimes, such as beautiful visualizations (see here) that actually have practical applications, or mathematical formulas, see for instance here.

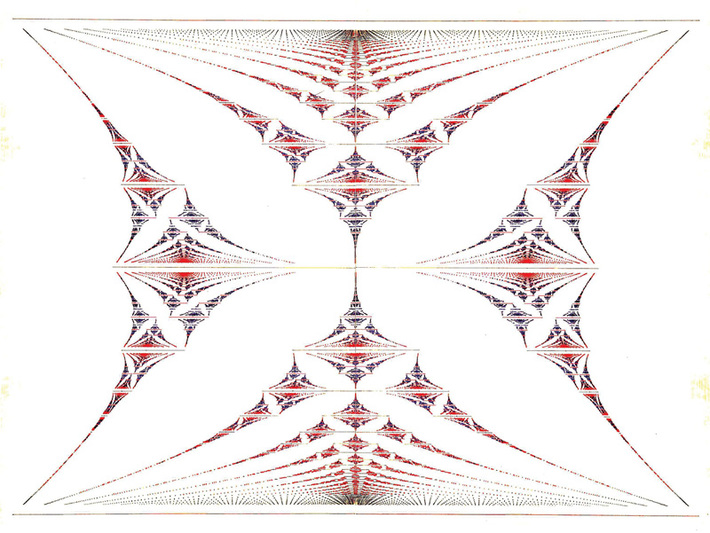

The picture at the top of this article can be found here. It represents the energy of electrons in an atomic lattice, and it is known as the butterfly fractal. It is also associated to special continued fractions. The author, Douglas Hofstadter, a physicist, is the one who wrote the masterpiece book Gödel, Escher, Bach, published initially in 1979. In his book, he claims some of his friends see this image as a picture of God. The book is all about AI, and everyone interested in AI should read it, despite being published for the first time about 40 years ago. In 1988, I proved one of the recursions mentioned in his book, see my article in Journal of Number Theory, here. I would also consider the typesetting system LaTex, created by Donald Knuth (famous computer scientist), as another piece of art, with very practical applications.

Then there is another way machine learning is related to arts. Music, paintings, videos (movies) and even culinary masterpieces, can be designed by AI, whether or not the code that produces these artistic creations, is dull and boring, or artistically written.

To receive a weekly digest of our new articles, subscribe to our newsletter, here.

About the author: Vincent Granville is a data science pioneer, mathematician, book author (Wiley), patent owner, former post-doc at Cambridge University, former VC-funded executive, with 20+ years of corporate experience including CNET, NBC, Visa, Wells Fargo, Microsoft, eBay. Vincent is also self-publisher at DataShaping.com, and founded and co-founded a few start-ups, including one with a successful exit (Data Science Central acquired by Tech Target). You can access Vincent’s articles and books, here. A selection of the most recent ones can be found on vgranville.com.