A big problem with the “Data Strategy” conversation is that many organizations think of a “Data Strategy” as a deliverable, not a journey. A Data Strategy, like a Business Strategy, should ebb and flow depending upon what is “valuable” to the organization given the current business environment. And the current business environment is constantly changing.

Today, we are seeing a confluence of disruptive changes and challenges driven by:

- Decreasing product and service margins

- Disruptions to supply chain, materials pricing, and supply chain predictability

- Spiraling energy and labor costs

- Fluctuating financial markets impacting the availability of capital

- Inflationary pressures impacting consumer confidence

Shouldn’t your data strategy be as flexible and relevant as your business environment? I think I smell a lesson in economics coming on…

The Data Strategy – Business Strategy Disconnect

Many organizations are struggling to build a data strategy that business leaders find compelling. Business leaders are frustrated because it takes IT so long to deliver the data and analytics that underpin the delivery of meaningful, relevant, timely business outcomes. And the IT and Data teams are frustrated because they cannot get the business financial commitment and organizational attention necessary to clearly articulate and commit to where and how data and analytics can impact the business.

Part of the problem is that business leadership has been taught to expect expensive, lengthy, complex IT projects that take years to deliver, where business leadership then hopes that whatever squeezes out at the end of that project is actually something that can deliver improved business outcomes. This “Big Bang” approach is the result of organizations that have historically sought competitive advantage through Economies of Scale.

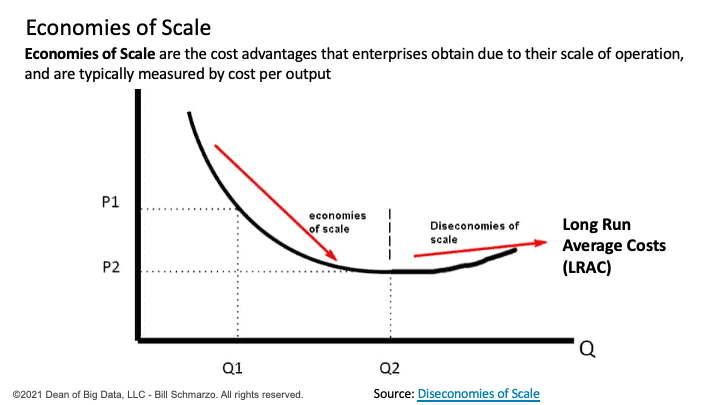

Economies of Scale are the cost advantages that enterprises obtain due to their scale of operation and are typically measured by reduced cost per output (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Source: “Economies of Scale”

Traditionally, large organizations have leveraged economies of scale and the “Big Bang” approach to lock smaller players and new competitors out of markets while tying up key suppliers. And traditionally, that has been an incredibly successful business strategy.

For example, ERP projects were ideal for these “Big Bang” implementations because the ERP projects were implementing standardized “best practices” in areas such as finance, manufacturing, logistics, sales, marketing, and human resources.

The Economies of Scale approach works great in a world where things don’t change; in a world where you don’t have new pandemics, new wars, new technology disruptions, new social challenges, new environmental mandates, new economic disruptions, and new political turmoil compounded by rapidly changing customer and organizational expectations based upon consumer personal experiences.

But the Economies of Scale has a menacing little brother lurking around the corner in a world of constant change. And that’s the Diseconomies of Scale.

Understanding the “Diseconomies of Scale”

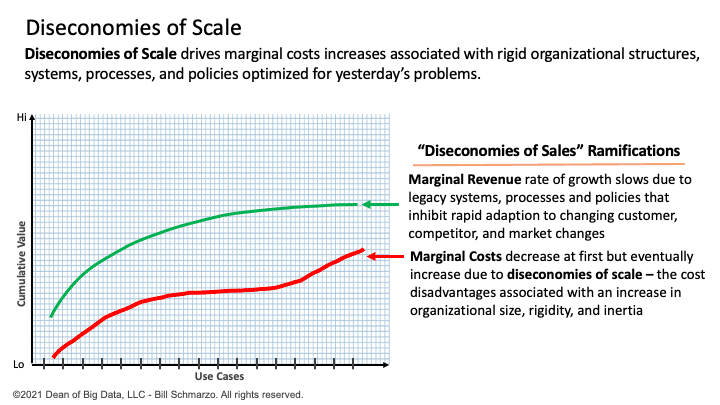

Diseconomies of Scale occur when long-run average costs (LRAC) start to rise with increased output associated with productivity challenges across large, dispersed organizations, lagging worker creative effectiveness throttled from mindless, repetitive tasks, and ineffective management from bloated command-and-control management structures (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Diseconomies of Scale

There are two ramifications of the Diseconomies of Scale:

- Marginal Revenue rate of growth slows due to legacy systems, processes, and policies that inhibit rapid adaption to changing customer, competitor, and market demands and opportunities.

- Marginal Costs decrease at first but eventually increase due to the compounding cost disadvantages associated with an increase in organizational size, rigidity, and inertia.

Diseconomies of Scale ramifications are further accentuated by an organization’s inability to rapidly adapt to changing customer, competitor, and market demands and challenges given a rigid business and operating model scaled to address yesterday’s problems framed by yesterday’s constraints.

Understanding the Economies of Learning

In knowledge-based industries, economies of learning are more powerful than economies of scale. And soon, every industry will be a knowledge-based industry.

We have entered an age where the “Economies of Learning” are more powerful than the “Economies of Scale”.

For me, the “Economies of Learning” concept originated with the “The Lean Startup” book by Eric Ries. In that book, the author introduced the concept of experimentation and incremental learning to become more efficient more quickly. For example, the author highlights the benefits of an incremental learning approach of stuffing newsletters into envelops one at a time versus the specialization of labor approach of folding all the newsletters first, then stuffing all the newsletters into the envelopes, and then sealing all the envelopes and finally stamping all the envelops.

- From a process perspective, you experiment and learn the most efficient method for stuffing envelopes that can then be immediately reapplied to improve business and operational outcomes.

- Also, you don’t have to wait until the end of the entire process to realize that you have made a costly or even fatal error (like folding all the newsletters the wrong way before you realize that they won’t fit into the envelopes).

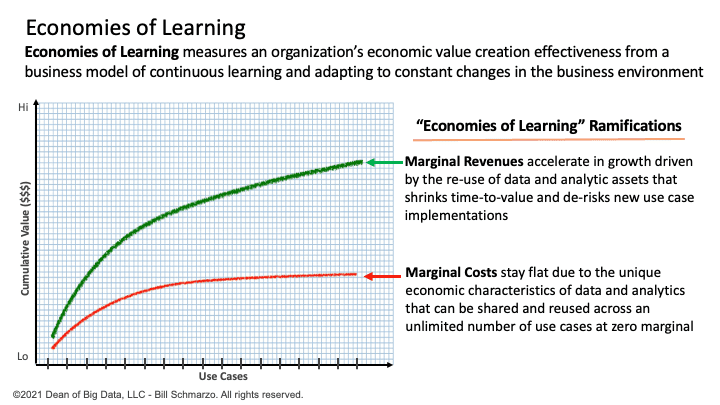

In knowledge-based industries, the benefits of the Economies of Learning are augmented by leveraging AI / ML to create assets, processes, and policies that continuously learn and adapt to their operating environment…with minimal human intervention. Organizations are exploiting the economies of learning to create data and analytic economic assets that appreciate, not depreciate, in value the more that they are used (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Economies of Learning

There are two important Economies of Learning ramifications:

- Marginal Costs stay flat due to the unique economic characteristics of data and analytics that can be shared and reused across an unlimited number of use cases at zero marginal costs.

- Marginal Revenues accelerate in growth driven by the re-use of data and analytic assets that shrinks time-to-value and de-risks new use case implementations.

To exploit the economies of learning, we need to take a different approach to build our data strategy. Instead of thinking of your data strategy as a one-time event with a static deliverable at the end, instead, think of your data strategy as a continuous journey that learns and evolves as the business environment evolves.

Leveraging a Use Case Approach to Build our Value-driven Data Strategy

Treating your data strategy as a static deliverable probably worked just fine in a world that never changes. However, today your data strategy must be a journey of continuous learning and adapting. Your data strategy must be as agile and dexterous as the business environment in which you operate.

That means we need to take a different approach to build an organization’s data strategy. We are going to move away from rigid “big bang” (economies of scale) data and analytics strategies towards an agile, value-driven data strategy driven by continuous, incremental learning and adapting (economies of learning).

I will cover how we can apply a Use Case approach to build an agile, continuously-learning, value-driven data strategy…in Part 2 of this blog.