Wirestock on Freepick

Mark Twain coined the term The Gilded Age when he published his 1873 novel The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. Between 1870 and 1914, the US experienced an unprecedented amount of industrial growth. Much of the resulting wealth accrued to the top one percent.

During the first Gilded Age, the top ten wealthiest people in the US held a total of $1.2 trillion (valued in 2006 dollars), according to Statista. Standard Oil capitalist John D. Rockefeller, the wealthiest man in the US, led the top ten, holding a total of $305.3 billion.

The Standard Oil Company trust during this period became a near monopoly. As a result, the Supreme Court ordered the dissolution of Standard Oil after a court case established the company was guilty of anticompetitive practices in 1911. This kind of US government trust busting–which also included the tobacco, railroads, sugar, and steel industries–brought an end to the Gilded Age by 1914.

Some other equally familiar names on the wealthiest list before the Gilded Age ended include steel magnate Andrew Carnegie ($281.2 billion), railroad baron Cornelius Vanderbilt ($168.4), the banking industry Mellon brothers Andrew and Richard (together worth $132.8 billion), and automotive industry pioneer Henry Ford ($54.3 billion).

The second gilded age

A second gilded age arguably began in 2013, when Jim Cramer, a CNBC investing TV show host, coined the term “FAANG” to describe the leading tech sector companies of the day: Facebook (now Meta), Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google (now Alphabet).

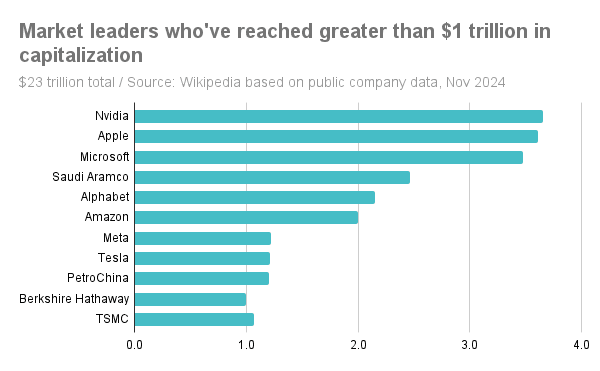

Apple was the first public US tech company to reach $1 trillion in market capitalization–in 2018.

As of November 2024, eleven public companies globally have reached $1 trillion in market capitalization. Three of these–Nvidia, Apple and Microsoft–have even reached over $3 trillion in market cap:

Some of these companies are leading or influential in multiple industry sectors, not just technology. Amazon, for example, continues to dominate the retail sector, but also has a presence in logistics, telehealth and digital health (including Amazon One Medical and Health Condition Programs).

Tesla is known as an automotive industry company, ranking second globally (at 13 percent) to Chinese electric vehicle maker BYD (at 22 percent) in EV market share in 2023, according to Statista. But Tesla could not be a market cap leader without its AI-driven innovations, including full self driving and the design of its own AI chips. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation (TSMC), also on the market cap leader list, manufactures the AI chips Tesla designs, as well as Apple’s AI chips.

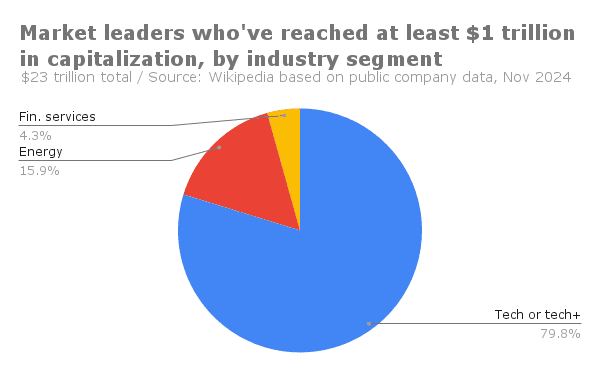

Data-driven, machine-assisted intelligence, whether it’s probabilistic machine learning, or deterministic, symbolic and rule-based, or a combination, was chiefly responsible for nearly 80 percent of the total of the top 11 market cap leaders in 2024. Energy companies rank a distant second by industry segment, making up nearly 16 percent of the total. Financial services (represented by Berkshire Hathaway alone, which has been investing in tech sector leaders for many years now) makes up just 4.3 percent of the total.

In April 2024, Forbes counted 342 billionaires in the tech sector as Forbes defines it, up from 313 in 2023. The top five tech billionaires using Forbes’ industry segmentation included Jeff Bezos (Amazon–$194 billion in net worth) , Mark Zuckerberg (Meta–$177 billion), Larry Ellison (Oracle–$141 billion), Bill Gates (Microsoft–$128 billion) and Steve Ballmer (Microsoft–$121 billion).

Forbes ranked Elon Musk (with Tesla in automotive, SpaceX in aerospace, Starlink in satellite internet, X in social media, et al.) as the richest person in the world at over $330 billion in net worth as of December. Forbes ranked Larry Page (Alphabet–$143 billion) and Sergey Brin (Alphabet–$136 billion) as #7 and #8 on its overall billionaire list.

The top public cloud providers associated with this tech sector billionaire list are also among the top ranked hyperscalers, investing the most in AI-grade and other data center infrastructure. Gartner ranks Amazon with Amazon Web Services, Microsoft with Azure, Alphabet with GCP, and Oracle with Cloud Infrastructure among its top five Strategic Cloud Platform Service providers.

Morgan Stanley estimated that hyperscaler capital expenditures in 2025 would reach $300 billion, led by Amazon and Microsoft spending upwards of $90 billion each. (See A few enterprise takeaways from the AI hardware and edge AI summit 2024 at https://www.datasciencecentral.com/a-few-enterprise-takeaways-from-the-ai-hardware-and-edge-ai-summit-2024/ for more information.)

The threat of AI-enabled surveillance capitalism

Monopolistic, anticompetitive behavior is one of the hallmarks of any gilded age. Most of the capital and human resources associated with AI innovation and investment are owned and controlled by small groups of people. But governments in the West in 2024 are much weaker than they were in the early 20th century, with only limited ability to counter the heightened power of the private sector.

It’s also the case that a concentrated digital marketplace can be more insidious and personally invasive than during the industrial age. In their article “Can you trust AI? Here’s why you shouldn’t” published in The Conversation in November 2024, Harvard’s cybersecurity guru Bruce Schneier and one of its data scientists Nathan Sanders used the term “surveillance capitalism” to describe the current state of private sector AI. They underscored the following points:

- AI platforms, intentionally or not, can be designed to favor the interests of developers over that of individual users.

- AI will acquire a much more intimate knowledge of a given user’s personal details to be able to act on the user’s behalf. From a security perspective, a user will therefore have to trust their personal assistant. In order to be able to trust such assistants, users “will need to be sure the AIs aren’t secretly working for someone else.”

- Monopolistic AI owners have built huge social media and ecommerce subscriber bases by offering “free” or very low cost services, but will need to monetize their investments eventually.

- For users, there’s no way to know right now if a given bot politically skews its output or even who actually owns the bot. “Most AIs,” the authors say, “fail to comply with the emerging European mandate” of the European Union’s proposed AI act.

The implication considering these realities is that users will have to fend for themselves when it comes to protecting themselves against monopolistic or at least oligopolistic AI for the foreseeable future.