Machine learning models grow more powerful every week, but the earliest models and the most recent state-of-the-art models share the exact same dependency: data quality. The maxim “garbage in – garbage out” coined decades ago, continues to apply today. Recent examples of data verification shortcomings abound, including JP Morgan/Chase’s 2013 fiasco and this lovely list of Excel snafus. Brilliant people make data collection and entry errors all of the time, and that isn’t just our opinion (although we have plenty of personal experience with it); Kaggle did a survey of data scientists and found that “dirty data” is the number one barrier for data scientists.

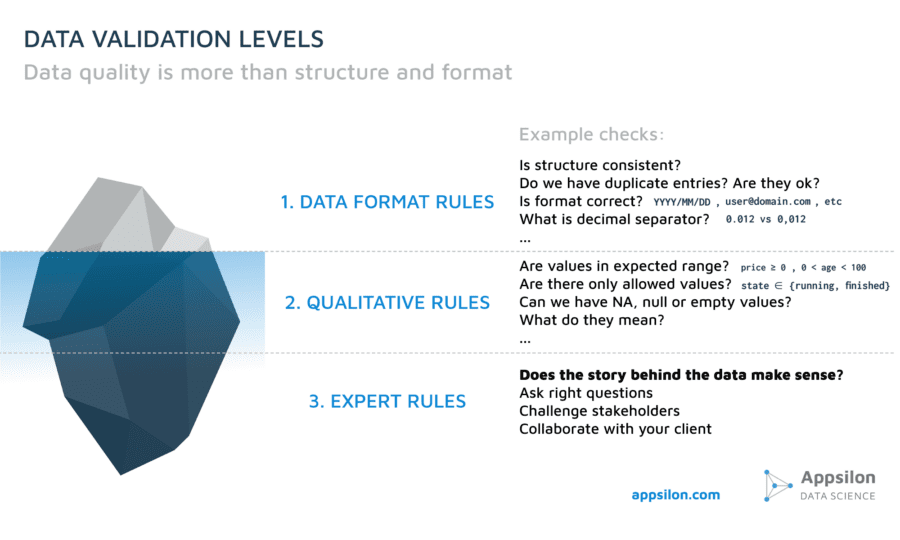

Before we create a machine learning model, before we create a Shiny R dashboard, we evaluate the dataset for a project. Data validation is a complicated multi-step process, and maybe it’s not as sexy as talking about the latest ML models, but as the data science consultants of Appsilon we live and breathe data governance and offer solutions. And it is not only about data format. Data can be corrupted on different levels of abstraction. We can distinguish three levels:

- Data structure and format

- Qualitative & business logic rules

- Expert logic rules

Level One: structure and format

For every project, we must verify:

- Is the data structure consistent? A given dataset should have the same structure all of the time, because the ML model or app expects the same format. Names of columns/fields, number of columns/fields, field data type (integers? Strings?) must remain consistent.

- Are we working with multiple datasets, or merged?

- Do we have duplicate entries? Do they make sense in this context or should they be removed?

- Do we have correct, consistent data types (e.g. integers, floating point numbers, strings) in all entries?

- Do we have a consistent format for floating point numbers? Are we using a comma or a period?

- What is the format of other data types, such as e-mail addresses, dates, zip codes, country codes and is it consistent?

It sounds obvious, but there are always problems and it must be checked every time. The right questions must be asked.

Level Two: qualitative and business logic rules

We must check the following every time:

- Is the price parameter (if applicable) always non-negative? (We stopped several of our retail customers from recommending the wrong discounts thanks to this rule. They saved significant sums and prevented serious problems thanks to this step… More on that later).

- Do we have any unrealistic values? For data related to humans, is age always a realistic number?

- Parameters. For data related to machines, does the status parameter always have a correct value from a defined set? E.g. only “FINISHED” or “RUNNING” for a machine status?

- Can we have “Not Applicable” (NA), null, or empty values? What do they mean?

- Do we have several values that mean the same thing? For example, users might enter their residence in different ways — “NEW YORK”, “Nowy Jork”, “NY, NY” or just “NY” for a city parameter. Should we standardize them?

Level three: expert rules

Expert rules govern something different than format and values. They check if the story behind the data makes sense. This requires business knowledge about the data and it is the data scientist’s responsibility to be curious, to explore and challenge the client with the right questions, to avoid logical problems with the data. The right questions must be asked.

Expert Rules Case Studies

I’ll illustrate with a couple of true stories.

Story #1: Is this machine teleporting itself?

We were tasked to analyze the history of a company’s machines. The question was, how much time did each machine work at a given location. We have the following entries in our database:

| Date | Machine ID | Hours of work | Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018-10-26 | 1234 | 1 | Warsaw |

| 2018-10-27 | 1234 | 2 | Cracow |

| 2018-10-28 | 1234 | 2 | Warsaw |

| 2018-10-29 | 1234 | 3 | Cracow |

| 2018-10-30 | 1234 | 1 | Warsaw |

We see that format and values are correct. But why did machine #1234 change its location every day? Is it possible? We should ask such a question of our client. In this case, we found that it was not physically possible for the machine to switch sites so often. After some investigation, we found that the problem was that the software installed on the machine had a duplicated ID number and in fact there were two machines on different sites with the same ID number. When we learned what was possible, we set data validation rules for that, and then we ensured that this issue won’t happen again.

Expert rules can be developed only by the close cooperation between data scientists and business. This is not an easy part that can be automated by “data cleaning tools,” which are great for hobbyists, but are not suitable for anything remotely serious.

Story #2: Negative sign could have changed all prices in the store

One of our retail clients was pretty far along in their project journey when we began to work with them. They already had a data scientist on staff and had already developed their own price optimization models. Our role was to utilize the output from those models and display recommendations in an R Shiny dashboard that was to be used by their salespeople. We had some assumptions about the format of the data that the application would use from their models. So we wrote our validation rules on what we thought the application should expect when it reads the data.

We reasoned that the price should be

- non-negative

- an integer number

- shouldn’t be an empty value or a string.

- within a reasonable range for the given product

As this model was being developed over the course of several weeks, suddenly we observed that prices were being returned as too high. It was actually validated automatically. It wasn’t like we spotted this in production, we spotted this problem before the data even landed in the application. After we saw this result in the report, we asked their team why it happened. It turns out that they had a new developer who assumed that discounts could be displayed as a negative number, because why not? He didn’t realize that some applications actually depended on that output, and assumed that it would be subtracting the value instead of adding It. Thanks to the automatic data validation, we could prevent loading errors into production. We worked with their data scientists to improve the model. It was a very quick fix of course, a no-brainer. But the end result was that they saved real money.

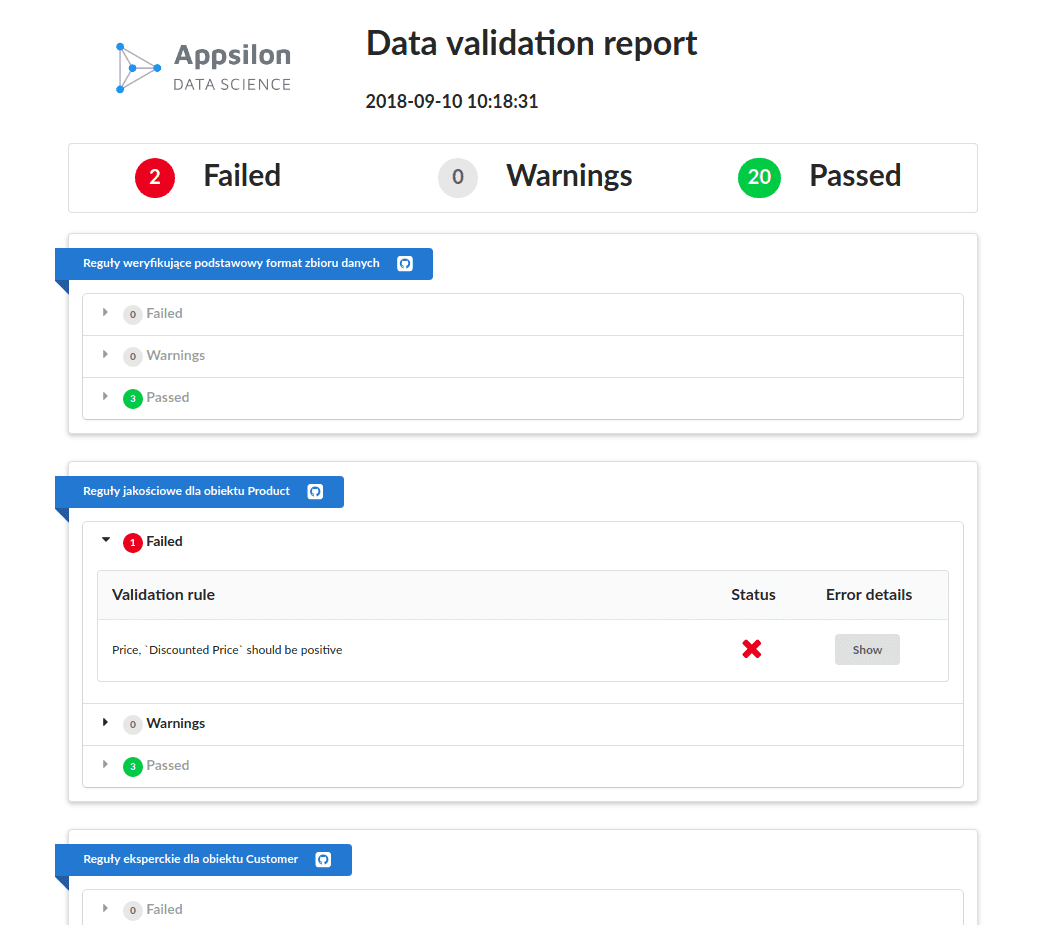

Data Validation Report for all stakeholders

Here is a sample data validation report that our workflow produces for all stakeholders in the project:

https://appsilon.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/data-verif-report–768×674.png 768w, https://appsilon.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/data-verif-report–… 1024w, https://www.datasciencecentral.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/data-verif-report.png 1054w” sizes=”(max-width: 570px) 100vw, 570px” pagespeed_url_hash=”185684064″ onload=”pagespeed.CriticalImages.checkImageForCriticality(this);” />

https://appsilon.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/data-verif-report–768×674.png 768w, https://appsilon.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/data-verif-report–… 1024w, https://www.datasciencecentral.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/data-verif-report.png 1054w” sizes=”(max-width: 570px) 100vw, 570px” pagespeed_url_hash=”185684064″ onload=”pagespeed.CriticalImages.checkImageForCriticality(this);” />

The intent is that the data verification report is readable by all stakeholders, not just data scientists and software engineers. After years of experience working on data science projects, we observed that multiple people within an organization know of realistic parameters for data values, such as price points. There is usually more than one expert in a community, and people are knowledgeable about different things. New data is often added at a constant rate, and parameters can change. So why not allow multiple people add and edit rules when verifying data? So with our Data Verification workflow, anyone from the team of stakeholders can add or edit a data verification rule.

Our Data Verification workflow works with the assertr package (for the R enthusiasts out there). Our workflow runs validation rules automatically – after every update in the data. This is exactly the same process as writing unit tests for software. Like unit testing, our data verification workflow allows you to more easily identify problems and catch them early; and of course fixing problems at an earlier stage is much more cost effective.

Finally, what do validation rules look like on the code level? We can’t show you code created for clients, so here is an example using data from the City of Warsaw public transportation system (requested from a public API). Let’s say that we want a real-time check on the location and status of all the vehicles in the transit system fleet.

library(assertr) source("utils.R") # Utils define functions like check_data_last_5min() or check_lat_in_warsaw() api_url <- "https://api.um.warszawa.pl/api/action/wsstore_get/?id=c7238cfe-8b1f-4c38-bb4a-de386db7e776" vehicle_positions <- jsonlite::fromJSON(api_url)[[1]] vehicle_positions %>% verify(title = "Each entry has 8 parameters", ncol(.) == 8, mark_data_corrupted_on_failure = TRUE) %>% assert(title = "Time is in format 'yyyy-mm-dd HH:MM:SS'", check_datetime_format, Time) %>% assert(title = "Data is not older than 5 minutes", check_data_last_5min, Time) %>% assert(title = "Latitude coordinate is correct value in Warsaw", check_lat_in_warsaw, Lat) %>% assert(title = "Longitude coordinate is correct value in Warsaw", check_lon_in_warsaw, Lon) %>% validator$add_validations("vehicles")

In this example, we want to ensure that the Warsaw buses and trams are operating within the borders of the city, so we check the latitude and longitude. If a vehicle is outside the city limits, then we certainly want to know about it! We want real-time updates, so we write a rule that “Data is not older than 5 minutes.” In a real project, we would probably write hundreds of such rules in partnership with the client. Again, we typically run this workflow BEFORE we build a model or a software solution for the client, but as you can see from the examples above, there is even tremendous value in running the Data Validation Workflow late in the production process! And one of our clients did remark that they saved more money with the Data Validation Workflow than with some of the machine learning models that were previously built for them.

Sharing our data validation workflow with the community

Data quality must be verified in every project to produce the best results. There are a number of potential errors that seem obvious and simplistic but in our experience to tend to occur often.

After working on numerous projects with Fortune 500 companies, we came up with a solution to the above 3-Level problem cluster. Since multiple people within an organization know of realistic parameters for datasets, such as price points, why not allow multiple people add and edit rules when verifying data? We recently shared our workflow at a hackathon sponsored by the Ministry of Digitization here in Poland. We took third place in the competition, but more importantly, it reflects one of the core values of our company — to share our best practices with the data science community.

https://appsilon.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/hackathon-768×576.jpeg 768w, https://appsilon.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/hackathon-1024×768…. 1024w, https://www.datasciencecentral.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/hackathon.jpeg 1200w” sizes=”(max-width: 600px) 100vw, 600px” pagespeed_url_hash=”2098616741″ onload=”pagespeed.CriticalImages.checkImageForCriticality(this);” />

https://appsilon.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/hackathon-768×576.jpeg 768w, https://appsilon.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/hackathon-1024×768…. 1024w, https://www.datasciencecentral.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/hackathon.jpeg 1200w” sizes=”(max-width: 600px) 100vw, 600px” pagespeed_url_hash=”2098616741″ onload=”pagespeed.CriticalImages.checkImageForCriticality(this);” />

Pawel and Krystian accept an award at the Ministry of Digital Affairs Hackathon

I hope that you can put these take-aways in your toolbox:

- Validate your data early and often, covering all assumptions.

- Engage a data science professional early in the process

- Leverage the expertise of your workforce in data governance strategy

- Data quality issues are extremely common

In the midst of designing new products, manufacturing, marketing, sales planning and execution, and the thousands of other activities that go into operating a successful business, companies sometimes forget about data dependencies and how small errors can have a significant impact on profit margins.

We unleash your expertise about your organization or business by asking the right questions, then we teach the workflow to check for it constantly. We take your expertise and we leverage it repeatedly.

https://appsilon.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/data-quality-iceberg-768×461.png 768w, https://appsilon.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/data-quality-iceber… 1024w” sizes=”(max-width: 773px) 100vw, 773px” pagespeed_url_hash=”1999022925″ onload=”pagespeed.CriticalImages.checkImageForCriticality(this);” />

https://appsilon.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/data-quality-iceberg-768×461.png 768w, https://appsilon.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/data-quality-iceber… 1024w” sizes=”(max-width: 773px) 100vw, 773px” pagespeed_url_hash=”1999022925″ onload=”pagespeed.CriticalImages.checkImageForCriticality(this);” />

You can find me on Twitter at @pawel_appsilon.

Originally posted on Data Science Blog.