Summary: Sensors that know how you feel? Sensors that want to change the way you feel? When did that happen and better yet how?

We’re getting used to sensors finding out what we’re doing. Apparently they are now sufficiently sophisticated that they can even tell if I’m sitting up straight (yes Mom – BTW using a camera is almost cheating, you should be able to do this with just an accelerometer and a gyro).

We’re getting used to sensors finding out what we’re doing. Apparently they are now sufficiently sophisticated that they can even tell if I’m sitting up straight (yes Mom – BTW using a camera is almost cheating, you should be able to do this with just an accelerometer and a gyro).

But what if I told you that those same IoT sensors can tell how you feel? And now they’re even being programmed to change the way you feel! A little creepy? Feeling manipulated? Hang on to your hat because it’s about to get worse or better depending on your point of view.

Mood Science

First of all I didn’t even realize that ‘mood science’ is a real thing. Turns out it’s been going on a long time in design circles where designers and architects in particular have been making informed guesses at what chills us out. Blue rooms relax. Red rooms stimulate and arouse. Pink rooms are most soothing.

Interesting note: For years many prisons have been painting their walls bright pink based on early findings that prison inmates’ tempers were soothed when placed in pink-walled cells. For what it’s worth these generalizations about room color have all now been overturned by the new practitioners of ‘mood science’.

I’ve been tracking the uses of IoT sensors particularly those with human interaction (think Fitbit) but I didn’t see the big picture until I came across this article “Design for Mood: Twenty Activity-Based Opportunities to Design for Mood Regulation” by Pieter M. A. Desmet, a member of the Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering, Delft University of Technology. This is one of those articles you know you should trust because it contains a reference bibliography of 169 learned articles.

For the most part it seems that in academic circles the desire to determine how to ‘regulate mood’ is pretty benign and generally couched in terms like improving subjective well-being. After all who doesn’t want an extra helping of well-being?

Then I found it. About three pages in, buried in the text:

- Mood influences consumer behavior. Research has demonstrated that consumer mood influences buying behavior, product preference, and purchase decisions.

- When evaluating new products, people do so more favorably when in a good mood than when in a bad mood.

- Mood influences user behavior. For example, when using new products, individuals in a bad mood tend to explore fewer interaction possibilities than those who are in a good mood.

- A good mood increases one’s willingness and motivation to adopt and use new technologies.

OK, now it’s clear. Just sending me a coupon when I’m standing next to the new flat screens isn’t nearly enough. “They” want to know how I’m feeling, and better yet to make me feel in a way that positively disposes me to buy.

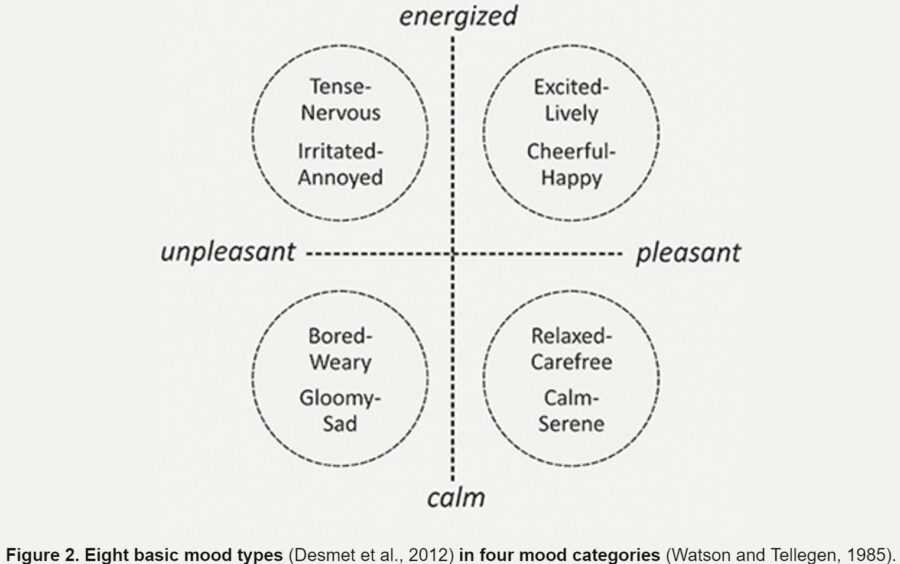

One more piece of foundational information before we move on to how this works. Turns out that monitoring and manipulating mood (feelings) through just four quadrants and eight basic mood types is enough to make this happen.

When it comes time to model, one of these eight states will be our dependent target variable.

How It Works

How would sensors go about detecting mood? It’s all about cleverly combining and interpreting the signals. This is a fairly new field studying how to fuse sensor data to make it context aware. Take for example heart rate as measured by a wearable sensor.

Dr. José Fernández Villaseñor is a medical doctor and electrical engineer studying the field of emotion analysis using sensors. His research shows the rate at which heart rate increases can differentiate between exercise and increases due to adrenalin from excitation based on the slope of the increase. Turns out that Heart Rate Variability (HRV) is one of the prime tells that can be used to differentiate one mood from another.

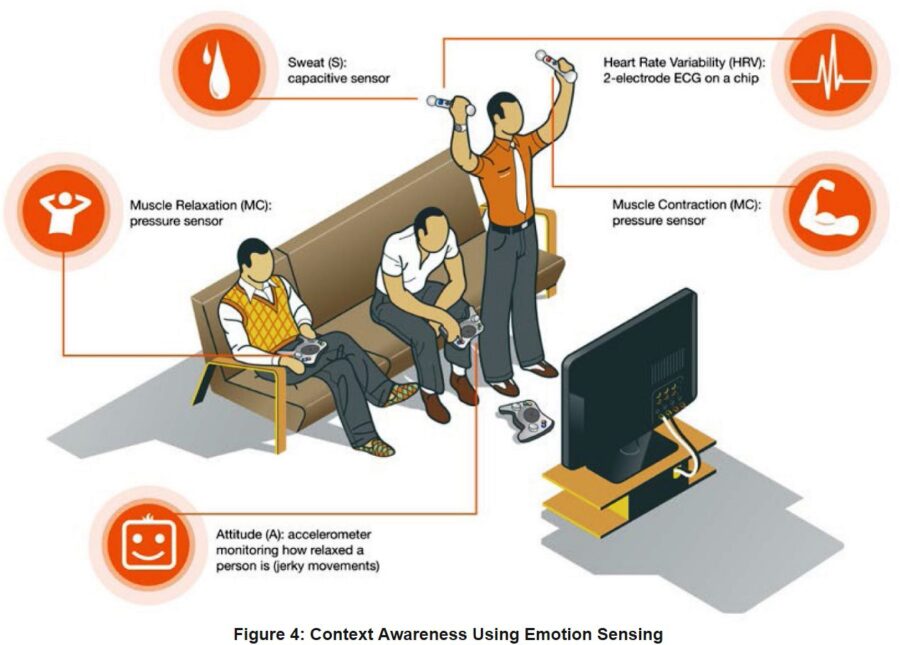

Here’s a simple example of how your Xbox or PS4 can not only tell how you’re feeling but manipulate those feelings.

image source: mouser.com

You are playing a driving game. Your game controller may contain sensors that can detect:

- Muscle relaxation (MR)—via a pressure sensor.

- Heart rate variability (HRV)—via a two-electrode ECG on a chip.

- Sweat (S)—via a capacitive sensor.

- Attitude (A)—via an accelerometer monitoring a person’s state of relaxation (jerky movements vs. steady hands).

- Muscle contraction (MC)—via a pressure sensor.

Suppose the combination of increased pressure on the controller, sweat, and the jerkiness of your motions (from the accelerometer) could be correlated (modeled) against your performance in the game.

Pressure and sweat increase. Jerkiness increases. Your game platform infers that you are both excited and stressed. Your score is just OK. To encourage you to play more, the system adjusts the difficulty of controlling the steering, braking, and the behavior of the other cars to reduce difficulty.

Your performance and score improves. Pressure and sweat decrease and your hand movements become smoother. The platform interprets that you are more relaxed and are mastering the game at this level. To keep you involved it increases excitement by making input controls and the behavior of competing cars more difficult.

You’ve just been gamed in the new world of IoT mood manipulation.

It’s Not Just About Wearables

In a sense, if you’re worried about the intrusiveness of this technology you would think that wearables offer their own defense – just don’t wear them (leave the Fitbit at home). Problem is it’s not just wearables. There are at least four categories of things that supply data about ourselves, many of which you may not have thought of in this way.

Wearables:

Wearables is a big one. It’s not just where you are and how fast you got there (GPS, accelerometers, altimeters, thermistors, gyros) it’s also sensors that measure physiological signals such as heart rate, skin conductance and temperature, and respiratory rate. These already include finger rings, ear rings, wristwatches, wrist and arm bands, and gloves. Soon to come, sensorized garments including shirts, shoes, and underwear.

Wearables is a big one. It’s not just where you are and how fast you got there (GPS, accelerometers, altimeters, thermistors, gyros) it’s also sensors that measure physiological signals such as heart rate, skin conductance and temperature, and respiratory rate. These already include finger rings, ear rings, wristwatches, wrist and arm bands, and gloves. Soon to come, sensorized garments including shirts, shoes, and underwear.

Take a look at the W/Me wearable wellness monitor introduced in 2013 that claims to measure the four basic mood states: passive, excitable, pessimistic, and anxious.

Natural-Contact Sensors

These are sensors that are integrated into the devices and particularly the surfaces of objects we regularly come in contact with. Likely you are interacting with these objects, not just brushing up against them. How about the steering wheel of your car that could easily have these sensors embedded and also transmit information about the smoothness or jerkiness of your movements.

It could be a chair that infers your stress or relaxation or a pen, cell phone, or mouse that can detect moods like stress, nervousness, and excitement based on hand movement. Even your keyboard can give you away by interpreting the strength and cadence of your keystrokes or how many times you use the backspace key.

Non-Contact Sensors

Anything with a camera or a microphone: computer, phone, TV, or game console that could use visual signal processing (deep learning) to record facial and voice expression, body posture, pupil diameter, and eyelid closure patterns. Law enforcement is hard at work adopting facial and emotion detecting software.

Self Expression

Sometimes we just tell machines how we feel. I frequently tell my alarm clock how I feel when I give it a rough slap (there could be a sensor in there warning my family I’m in a bad mood when I come out for breakfast). About 8 years ago Philips developed a ‘mood pad’ for hotel rooms that let you pick a mood (romantic, restful, let me sleep) that controlled ambient lighting. And if you look in your app store, I’m sure you can find an app for creating a mood journal or for evaluating how you feel right now. Who’s receiving that signal?

What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

This question is almost too rhetorical to even ask. If you want to make me more likely to buy something, OK, maybe I can live with that. And if it makes my game play more interesting that might go on the good list. If your car tells you you’re suddenly suffering from road rage that could be helpful. And certainly there are applications in healthcare, mental care, and elder care that we can easily applaud.

But when it comes to manipulating me I really want to know who’s doing it and with what motive. What could the government or the IRS be learning about me or trying to make me do? I don’t want to seem alarmist. Sometimes the best thing we can do is just make ourselves aware that this is happening. Maybe there will be an on-package or on-screen disclaimer (probably buried deep in the EULA).

This is one of those technological advances that delights me as a data scientist and disturbs me as a citizen and human being. Like all technological advances this one’s out of the bottle and trying to get it back in would make the loaves and fishes look like child’s play. As much as anything, I just want to know if I’m getting some quid for my quo.

About the author: Bill Vorhies is Editorial Director for Data Science Central and has practiced as a data scientist and commercial predictive modeler since 2001. He can be reached at: