Originally posted here, where you can see all the graphics.

There has been much in the news lately about the next wave of MT technology driven by a technology called deep learning and neural nets (DNN). I will attempt to provide a brief layman’s overview about what this is, even though I am barely qualified to do this (but if Trump can run for POTUS then surely my trying to do this is less of a stretch). Please feel free to correct me if I have inadvertently made errors here.

To understand deep learning and neural nets it is useful to first understand what “machine learning” is. Very succinctly stated machine learning is the “Field of study that gives computers the ability to learn without being explicitly programmed” according to Arthur Samuel.

Machine learning is a sub-field of computer science that evolved from the study of pattern recognition and computational learning theory in artificial intelligence. Machine learning algorithms iteratively learn from (training) data by generalizing their experience (“analysis” of the data) into predictive models. These models allow computers to find insights that might be difficult or even impossible for humans to find. In the case of MT the objective is to build predictive models that translate new source data based on “knowledge” it has gathered from translation memory and other natural language data it is shown (trained on). Think of it simply as a branch of statistics and applied computing, designed for and enabled by a world of big data. For example, to some extent SMT is a more flexible and generalized implementation of the older TM technology, which can guess at new sub-segments based on learning obtained from its training experience.

Machine Learning is the field that studies how to make computers learn on their own (unsupervised), and covers a lot of ground in computing beyond text and MT applications, and most recently has had amazing success with image data. A Machine Learning algorithm is a computer program that teaches computers how to program themselves so that we don’t have to explicitly describe how to perform the task we want to achieve. The information that a Machine Learning algorithm needs in order to write its own program to solve a particular task is a (large) set of known examples e.g. translation memory or radiology images together with resultant diagnoses.

Machine Learning is a big deal, perhaps even a really big deal.

Google CEO, Sundar Pichai, recently laid out the Google corporate mindset: “Machine learning is a core, transformative way by which we’re rethinking how we’re doing everything. We are thoughtfully applying it across all our products, be it search, ads, YouTube, or Play. And we’re in early days, but you will see us — in a systematic way — apply machine learning in all these areas.” Google is all in. Google believes that one day it will be used by all software engineers no matter what the field, and that it will “change humanity.”

But how is it used, in practice? Very roughly speaking there are three broad concepts that capture most of what goes on under the hood of a machine learning algorithm: feature extraction, which determines what data to use in the model; regularization, which determines how the data are weighted within the model; and cross-validation, which tests the accuracy of the model. Each of these factors helps us identify and separate “signal” (valuable, consistent relationships that we want to learn) from “noise” (random correlations that won’t occur again in the future, that we want to avoid). Every data set has a mix of signal and noise, and skill with these concepts will help you sort through that mix to make better predictions. This is a gross oversimplification and needs much more elaboration than is possible in this post.

Traditional AI methods of language understanding depended on embedding rules of language into a system, but in the Google SmartReply project, as with all modern machine learning, the system was fed enough data to learn on its own, just as a child would. “I didn’t learn to talk from a linguist, I learned to talk from hearing other people talk,” says Greg Corrado who developed SmartReply at Google. Corrado says that the approach requires a change in mindset for coders, from controlling everything directly to analyzing data, and even new hardware. The company even created its own chip, the Tensor Processing Unit, optimized for its machine-learning library TensorFlow.

Getting back to MT, it is useful to first look at how machine learning is used in SMT to better understand the evolution enabled by neural networks. The SMT model is generally made up of two (sometimes more) predictive models learned from “training data” which includes both representative bilingual data and monolingual data in the target language.

- SMT Translation Model – Learned from Bilingual Data (Translation Memory)

- Probabilistic mapping of equivalencies in source words and phrases with target language words and phrases through the Unsupervised Expected Model (EM) training and word and phrase alignment process.

- The Translation Model generates lots of possible translations

- Target Language Model – Learned from Monolingual Target Language Data

- Probabilistic model of relative fluency and general usage patterns in the target language

- The Target Language Model selects the “best” translations from a list of possible candidates

Even though this is essentially a probability maximization exercise (not really a translation), it can do surprisingly well, and translate new source data in the same domain quite accurately.

This link provides a relatively simple overview of the learning process in slides, and here is Norvig again, giving

a very clear 12 minute overview of how SMT works. Much of what we see today, as

phrase based SMT including Moses, is built with this kind of a learning approach. Even with many limitations this is a significant improvement over the older Rule Based MT systems where humans tried to codify and program the language pair.

Some of the most obvious problems include the following:

- Since this is a word based approach it is not as effective with character based languages (CJK) because of imperfect segmentation and tokenization issues.

- It has a very limited sense of context and is often quite mindlessly literal.

- It is not especially effective with language combinations that have varying morphology, non-contiguous phrases and syntactic transformations.

- It has limited success in scarce data scenarios and more data does not always drive improvement.

Deep Learning with Neural Networks to the rescue

Neural nets are modeled on the way biological brains learn. When you attempt a new task, a certain set of neurons will fire. You observe the results, and in subsequent trials your brain uses feedback to adjust which neurons get activated. Over time, the connections between some pairs of neurons grow stronger and other links weaken, laying the foundation of a memory. A neural net (DNN) essentially replicates this process in code.

Neural Nets are a specific implementation of a Machine Learning algorithm. In a way Neural Nets allow one to extract “more knowledge” from the training data set and access deeper levels of “understanding” from the reference data. Neural networks are complex, computationally intensive and hard to tune as machines may see multiple layers of patterns that don’t always make sense to a human, yet can be surprisingly effective in building prediction models of astonishing accuracy.

Again, Andrew Ng explains

why this technology that has been around for 20 years, has reached its perfect storm moment. Basically because the availability of really big data + high performance computing + evidence of successful prediction in image processing suggest that it can, and could work, in solving complex problems in many other areas where standard programming approaches would be impractical.

Deep Neural Nets can have a large number of hidden layers and are able to extract much deeper related features from the data. Recently, deep neural networks have performed particularly well for

image recognition problems . Deep neural networks have become extremely popular in more recent years due to their

unparalleled success in image and voice recognition problems. Neural Nets have been successful with sequence recognition problems (gesture, speech, ATM handwritten check text recognition), medical diagnosis, financial trading systems, visualization and e-mail spam filtering.

Just as with dirty data SMT, one of the biggest reasons why neural networks may not work is because people do not properly pre process the data being fed into the neural network. Data normalization, removal of redundant information, and outlier removal should all be performed to improve the probability of good neural network performance. There are a variety of DNN techniques that solve different kinds of deep learning problems. An understanding of how these different approaches perform better under different constraints and different evaluation criteria is underway in the research community as we speak.

In particular, Neural Networks excel in cases where the strategy is not known ahead of time and instead must be discovered. In cases where this is NOT true and all that must be learned are the parameters for that strategy, there are algorithms that can find good solutions a whole lot faster and with fewer resources.

So in the MT context, the rationale behind using the neural network-based training is about discovering the hidden “reasons” behind the translation of the text in the training set; essentially, the machine may be “writing rules of linguistic relationship” automatically, and producing a more flexible engine by extracting more useful ”knowledge” from the existing training data. Note that these features are not necessarily the same features human linguists would use (parts of speech, morphology, syntax, transitivity, etc…) But these hidden layers have solved problems of great difficulty in image recognition and there is reason to believe that they can do this with NLP as well. Of course, this is easier said than done but that’s the basic reasoning and there is much research underway with Google, Facebook, Microsoft and Baidu (the big four) leading the way.

One DNN breakthrough example is WORD2VEC. Its creators have shown how it can recognize the similarities among words (e.g., the countries in Europe) as well as how they’re related to other words (e.g., countries and capitals). It’s able to decipher analogical relationships (e.g.,

short is to

shortest as

big is to

biggest), word classes (e.g.,

carnivore and

cormorant both relate to animals) and “linguistic regularities” (e.g., “

vector(‘king’) – vector(‘man’) + vector(‘woman’) is close to

vector(‘queen’)). Kaggle’s Howard calls

Google’s word2vec the “crown jewel” of natural language processing. “It’s the English language compressed down

to a list of numbers,” he said. The real benefit of this will take years to unfold as more researchers experiment with it to try and solve new NLP problems.

From the

data scientist’s perspective, MT aims to find for the source language sentence presented to it, the most probable target language sentence that shares the most similar meaning. Essentially, MT from the data scientists perspective is a sequence-to-sequence prediction task.

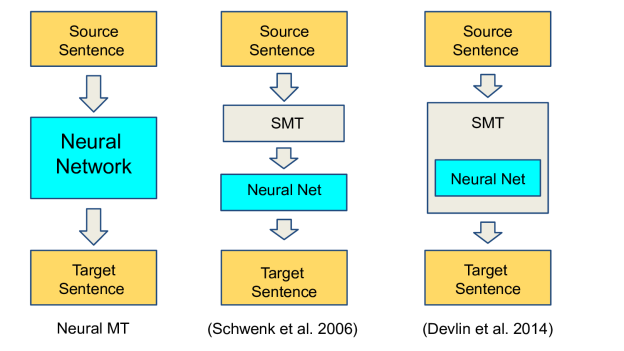

Indirect DNN application designs new features with DNNs in the framework of standard SMT systems, which consist of multiple sub-models (such as optimal translation candidate selection and more fluent and natural language models). For example, DNNs can be leveraged to represent the source language context’s semantics and better predict translation candidates. (The two columns shown to the right in the graphic above reflect an indirect implementation.)

The indirect application of DNNs in SMT aims to solve difficult problems in an SMT system with more accurate context modeling and syntactic/semantic representation e.g. Word Alignment in SMT which have two disadvantages: 1) The current process can’t capture the similarity between words, and 2) contextual information surrounding the word isn’t fully explored. Traditionally, translation rule selection is usually performed according to co-occurrence statistics in the bilingual training data rather than by exploring the larger context and its semantics. DNNs help to improve the process to consider context and semantics more effectively.

Language Model – The most popular language model is the count-based n-gram model described by Norvig and by the charts above. One big issue here is that data sparseness becomes severe as n grows. Using RecurrentNN ( a type of DNN) allows a better solution than the standard count-based n-gram model. All the history words available are applied to predict the next word instead of just n-1. This allows an SMT model to have a much better sense of context. The table below shows one view on how different types of DNNs can help address common SMT problems.

Statistical machine translation difficulties and their corresponding deep neural network solutions.

Word alignment FNN, RecurrentNN

Translation rule selection FNN, RAE, CNN

Reordering and structure prediction RAE, RecurrentNN, RecursiveNN

Language model FNN, RecurrentNN

Joint translation prediction ` FNN, RecurrentNN, CN

However, indirect application of DNNs makes the SMT system much more complicated and difficult to deploy.

Direct application (NMT) regards MT as a sequence-to-sequence prediction task and, without using any information from standard MT systems, designs two deep neural networks—an encoder, which learns continuous representations of source language sentences, and a decoder, which generates the target language sentence with source sentence representation. (Yes I really cannot figure out a way to say this in a more intelligible way.)

In contrast, direct application is simple in terms of model architecture: a network encodes the source sentence and another network decodes to the target sentence. Translation quality is improving, but this new MT architecture is far from perfect. There’s still an open question of how to efficiently cover more of the vocabulary, how to make use of the target large-scale monolingual data to improve fluency, and how to utilize more syntactic/semantic knowledge in addition to what is possible learn from source sentences.

How do DNNs improve translation quality?

For example, several algorithms can be applied to calculate the similarity between phrases or sentences. But they also capture much more contextual information than standard SMT systems, and data sparseness isn’t as big a problem. For example, the RecurrentNN can utilize all the history information in text that comes before the currently predicted target word; this is impossible with standard SMT systems.

Can DNNs lead to a big breakthrough?

- There have been recent breakthroughs but NMT is computationally much more complex. Because the network structure is complicated, and normalization over the entire vocabulary is usually required, DNN training is a time-consuming task. Training a standard SMT system on millions of sentence pairs only requires a day or two, whereas training a similar NMT system can take several weeks, even with powerful GPUs.

- Currently it is hard to understand and pinpoint why it is better or worse than SMT – i.e. error analysis is problematic but experimentation is underway at the big four listed above.

- Limited reasoning and remembering capabilities and suffers with rare words and long sentences.

- A straightforward Moses-like toolkit that fosters more experimentation is desperately needed but will take at least a year or two to become widely available.

- NMT produces much more natural sounding translations than SMT claim Facebook, Google and Microsoft.

- Better ability to handle idiom and metaphor as the Facebook team is claiming.

Purely neural machine translation (NMT) is the new MT paradigm. The standard SMT system consists of several sub-components that are separately optimized and normally implemented in a production pipeline. In contrast, NMT employs only one neural network that’s trained to maximize the conditional likelihood on the bilingual training data. The basic architecture includes two networks: one encodes the variable-length source sentence into a real-valued vector, and the other decodes the vector into a variable length target sentence.

Experiments report similar or superior performance in English-to-French translation compared to the standard phrase-based SMT system. The MT network architecture is simple, but it has many shortcomings. For example, it restricts tens of thousands of vocabulary words for both languages to make it workable in real applications, meaning that many unknown words appear. Furthermore, this architecture can’t make use of the target large-scale monolingual data. Attempts to solve the vocabulary problem are heuristic, e.g. they use a dictionary in the post-processor to translate the unknown words.

However in spite of these issues, as Chris Wendt at Microsoft says: “Neural networks bring up the quality of languages with largely differing sentence structure, say English<>Japanese, up to the quality level of languages with similar sentence structure, say English<>Spanish. I have looked at a lot of Japanese to English output: Finally actually understandable.”

Jeff Dean at Google is excited about his own

team’s effort to push things forward with NMT. “This is a model that uses only neural nets to do end-to-end language translation,” he says. “You train on pairs of sentences in one language or another that mean the same thing. French to English say. You feed in English sentences one word at a time, boom, boom, boom… and then you feed in a special ‘end of English’ token. All of a sudden, the model starts spitting out French.”

Dean shows a head-to-head comparison between the neural model and Google’s current system — and his deep learning newcomer one is superior in picking up nuances in diction that are key to conveying meaning. “I think it’s indicative that if we scale this up, it’s going to do pretty powerful things,” says Dean.

Alan Packer at FaceBook said they believe

neural networks can learn “the underlying semantic meaning of the language,” so what is produced are translations “that sound more like they came from a person.” He said neural network-based MT can also learn idiomatic expressions and metaphors, and “rather than do a literal translation, find the cultural equivalent in another language.” Machine Learning is

deeply embedded into the FaceBook system infrastructure and we should expect many new breakthroughs.

Tayou is the only language industry MT vendor who seems to have experimented with NMT thus far, and they

have mixed results, that are presented here. These early results are useful to understand the challenges with early NMT, but these experiments are not useful to conclusively conclude on the real the potential of NMT to outperform SMT or not. The development tools will get better and the same experiments described here could yield different outcomes in future, as tools improve.

So while there are indeed challenges to getting NMT launched in a broad and pervasive way, there are many reasons to march forward. We see the largest Internet players including Microsoft, Google, FaceBook and Baidu are all working with DNNs and all have NMT initiatives in motion. Microsoft has already deployed pure neural networks on mobile translation apps for Android and iOS. Of course with a very small and limited vocabulary but this will only grow and evolve.

I doubt very much that phrase based SMT is going away to quietly die in the short term (LT 5 years). But as supercomputing access becomes commonplace, and as NMT fleshes out with more comprehensive support tools, the same way that SMT did (which takes some years), we could see a gradual transition and evolution to this new kind of MT. There is enough actual evidence of success with NMT to generate real excitement, and I expect we will see a super-Moses-like kit to build NMT systems appear within the next 12 months. This will foster more experimentation and possibly discover new pathways to better automated translation. All this only points to improving MT, albeit gradually, and while MT is a truly difficult engineering problem, the best minds in the world are far from finished on what is possible to improve MT using machine intelligence technology. The emergence of NMT also points to the high likelihood of obsolescence for those who like to keep everything on-premise or the desktop. The best MT solutions will likely happen in the cloud and will be unlikley to be possible at all on the desktop.

MT naysayers should be aware, that the mindset that most of these MT researchers have in place, can be encapsulated by the following statement originally made by Thomas Edison: “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.” It will indeed get better.