And 92 percent of all (positive) integers have a factor under 1,000. And how many have a factor under 6? Can you guess the answer? Read more to find out.

Clearly, the vast majority of big numbers have small factors. Also, the chance to be a prime becomes incredibly small, the bigger the number. I stumbled upon these problems when looking for new algorithms to factor a product of two large primes (more on this coming soon.) I then decided to find out what the proportion of integers having a factor under n, is.

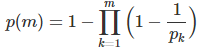

To answer this question, let’s first define p(m) as the proportion of integers that are divisible by one (or more) of the first m prime numbers. One can easily show that

where the product is over the first m prime numbers. In particular, the proportion of integers with a factor under 6 is p(3) = 1 – (1 – 1/2)(1 – 1/3) (1 – 1/5) = 73%. The above mathematical formula can easily be derived, using arguments similar to those in my article A Beautiful Probability Theorem.

where the product is over the first m prime numbers. In particular, the proportion of integers with a factor under 6 is p(3) = 1 – (1 – 1/2)(1 – 1/3) (1 – 1/5) = 73%. The above mathematical formula can easily be derived, using arguments similar to those in my article A Beautiful Probability Theorem.

To answer the more general question about the proportion of integers having a factor under n, one must choose m such that the last prime in the above product is the largest prime number smaller than n. Using the prime number theorem, it is easy to get an approximation for m as n tends to infinity. Also, taking the logarithm of the product, one can finally answer the question using approximations based on the prime number theorem. I will leave it to the reader to find the asymptotic formula and post it here in the comment section below.

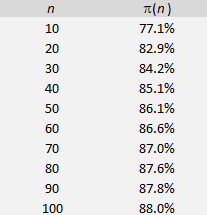

Using the exact formula for p(m), it is also easy to built a table:for the proportion p(n) of positive integers with a factor under n, see table below:

Other Problems Involving Factoring

Here, by divisor, I mean a non-trivial divisor. For instance, the largest divisor of 45 is 15, not 45. Study the following recurrence relationships:

- f(n+1) is the largest prime factor of 3 f(n) + 1, with f(1) = 1.

- Same if f(n+1) is defined as the largest prime factor of 2 f(n) + 5, with f(1) = 1.

Are all these functions turning periodic, beyond some n?

What about

- f(n+1) is the largest divisor of {f(n)}^2 + 1, with f(1) = 1.

- f(n+1) is the largest divisor of {f(n)}^2 – 2, with f(1) = 3.

Why is the last function growing so fast? Are prime numbers over-represented among the values of f(n)? Can these functions be used to build large prime numbers? Is it possible that for some n, {f(n)}^2 – 2 (say) does not have a non-trivial divisor, which means that it is a prime number and that f(n+1) does not exist?

Top DSC Resources

- Article: Difference between Machine Learning, Data Science, AI, Deep Learnin…

- Article: What is Data Science? 24 Fundamental Articles Answering This Question

- Article: Hitchhiker’s Guide to Data Science, Machine Learning, R, Python

- Tutorial: Data Science Cheat Sheet

- Tutorial: How to Become a Data Scientist – On Your Own

- Tutorial: Advanced Machine Learning with Basic Excel

- Categories: Data Science – Machine Learning – AI – IoT – Deep Learning

- Tools: Hadoop – DataViZ – Python – R – SQL – Excel

- Techniques: Clustering – Regression – SVM – Neural Nets – Ensembles – Decision Trees

- Links: Cheat Sheets – Books – Events – Webinars – Tutorials – Training – News – Jobs

- Links: Announcements – Salary Surveys – Data Sets – Certification – RSS Feeds – About Us

- Newsletter: Sign-up – Past Editions – Members-Only Section – Content Search – For Bloggers

- DSC on: Ning – Twitter – LinkedIn – Facebook – GooglePlus

Follow us on Twitter: @DataScienceCtrl | @AnalyticBridge

Interesting way to view prime numbers and composite integers. I am working on a thesis that shows where Euler’s Product can be derived using Fourier series analysis. I know that Fourier and Euler wrote one another back in those days, but I don’t think that Fourier or Euler ever knew that Fourier series analysis could be used to discover the periodic harmonic nature of Euler’s Product and thus the behavior of prime numbers themselves. This is, by far, one of the most fascinating mathematics problems that I ever encountered.